As many of you will know/may have surmised, I am working on a new monograph on tiny people and miniature worlds in children’s fantasy. My previous posts on Selma Lagerlöf’s The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, T.H. White’s Mistress Masham's Repose, and B.B.’s The Little Grey Men are small parts of that larger project. These previous posts focused on how zooming in on tiny scale can enable a re-imagined relationship with the natural world, or how such fantasy texts can engage with serious ethical questions and historical settings. Today’s piece brings in another aspect of miniature fantasies: the way such books play with (and often critique) human (and specifically grown-up) material entanglements with all things tiny. In this example, we’re going to look at miniature books, extraordinary real objects in the real world, and a bit of a niche research area in which I have been interested for a while now.

In 2017-2018 I was involved in an interdisciplinary project that created one of the world’s smallest books: a tiny reproduction of Lewis Carroll’s children’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). All 78 pages and 26,764 words of the story were transposed on to a tiny silicon chip, with each page just the width of a human hair (60 microns). Each individual letter was just two microns high, and made from pure gold. You can read more about this project here. As the website of the project was being launched, I also curated a small exhibition of some of the best miniature books held at the Special Collections of the University of Glasgow. All items and my curatorial notes can be found here. I also ended up appearing on BBC One’s TV programme Bargain Hunt, in their special “Tiny Treasures” episode, showcasing some of these minuscule books. If you’re in the UK, you can watch this episode here (I am on from around 06:10). There’s also a brief teaser from that episode available here.

What are miniature books? Origins, Sizes and Classifications

There is a long tradition of miniature books, from tiny medieval illuminated manuscripts, to the Victorian and Edwardian craze for minuscule printed books. We could even regard cuneiform tablets from ancient Mesopotamia (measuring 1⅝ by 1 ½ inches, and dating from 2000BC) as the earliest miniature books, though “preminiature books” may be a more accurate term.1

Certainly the desire or wish for having canonical or iconic texts in miniature format goes back a long way. The idiomatic phrase “in a nutshell”, defined by the OED as “suggesting great condensation, brevity, or limitation”2, was originally an allusion to a copy of Homer’s Iliad, which was supposedly small enough to be enclosed in the shell of a nut. In Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, we read:

Instances of acuteness of sight are to be found stated, which, indeed, exceed all belief. Cicero informs us, that the Iliad of Homer was written on a piece of parchment so small as to be enclosed in a nut-shell.3

What is ironic here is that Cicero’s statement cannot be verified: it must have appeared in one of his works now long lost. Was really the Iliad ever contained in a nutshell, or was this just a rumour, or a dream?

In any case, size does matter with miniature books. For most collectors, the size of a miniature book should be no more than 3 inches (76 mm) in height, though there are exceptions to this rule, and also further classificatory sub-categories. Books of 3-4 inches in height are often labelled “macrominiatures”, “microminiatures” are ¼-1 inch in height, while “ultra-microminiatures” are less than ¼ inches in height.4

Is the attraction of miniature books part of a wider human interest in extremes? (e.g. the world’s highest building) Or is there a practical or artistic side to their allure? Curiosity has a role to play in the fascination with the minuscule, but most miniature books negotiate a fine line between the aesthetic and the practical. Miniature books are eminently portable: their owners could carry a small library in their pockets in eras well before e-books and smart phones. The convenience of carrying a tiny book for religious devotion or private study cannot be underestimated. Nevertheless, artistry and skill have often been an equal, if not greater, consideration. Some collectors will not accept miniature books that fulfil the 3-inch rule but are crudely produced, printed in large type, or ill-proportioned. Miniature books have been a prime way of showcasing craftsmanship, be it in miniscule handwriting on vellum, or tiny printing or engraving on paper.

But what happens when such books fall in the hands of little people in children’s fantasy texts? We’ll look at two examples: Mary Norton’s The Borrowers (the first of a series of 5 books and one short story), and Ann M. Martin and Laura Godwin’s The Doll People (also the first of a series of 4 books, and one picturebook).

Arrietty’s Library in The Borrowers

I am assuming here that most of my readers will have at least heard of Mary Norton’s The Borrowers, or at least will be familiar with one of its numerous adaptations. The story revolves around a small, nuclear family of little people,5 Pod, Homily, and their daughter, Arrietty, who live behind the wainscots of a big stately home at around the turn of the 20th century,6 and survive by “borrowing” tiny (and mostly trivial) foodstuffs and items from the “human beans” in the big house. During the novel we see Arrietty venturing out of her quiet, dusty, boring domestic setting to encounter the Great Outdoors, and to develop a complicated relationship with a human Boy who is a visitor at the house. The story has resonances with the “last of their race” narrative we often see in fantasies about little people, it explores scale (and scale reversal) in fascinating ways, and it poses all sorts of scientific and philosophical/ethical questions and dilemmas to the child reader.

I will be writing more about The Borrowers and its sequels in the next few weeks and months, but let me focus here on what I promised: the presence of miniature books in the narrative. As we first encounter the Borrowers, Pod, Homily, and Arrietty, and explore the ingenious ways they’ve used human detritus to construct their home, we are also very soon introduced to “Arrietty’s library”:

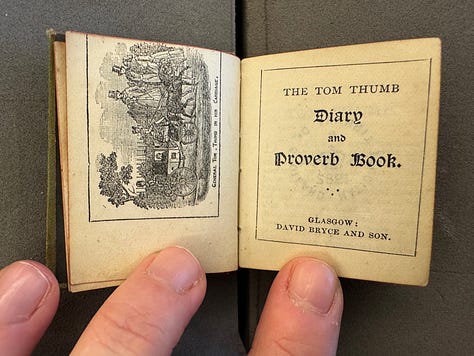

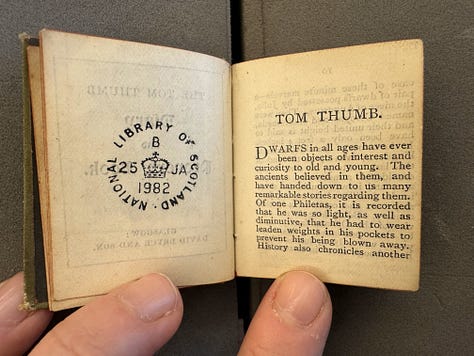

This was a set of those miniature volumes which the Victorians loved to print, but which to Arrietty seemed the size of very large church Bibles. There was Bryce's Tom Thumb Gazetteer of the World, including the last census; Bryce's Tom Thumb Dictionary, with short explanations of scientific, philosophical, literary, and technical terms; Bryce's Tom Thumb Edition of the Comedies of William Shakespeare, including a foreword on the author; another book, whose pages were all blank, called Memoranda; and, last but not least, Arrietty's favorite Bryce's Tom Thumb Diary and Proverb Book, with a saying for each day of the year and, as a preface, the life story of a little man called General Tom Thumb, who married a girl called Mercy Lavinia Bump. There was an engraving of their carriage and pair, with little horses the size of mice. Arrietty was not a stupid girl. She knew that horses could not be as small as mice, but she did not realize that Tom Thumb, nearly two feet high, would seem a giant to a Borrower. (The Borrowers, Chapter 2)

Miniature books were produced long before the 19th-century, of course, but “the Victorians”, as the narrator’s voice tells us, were particularly fond of such curiosities, both as feats of craftsmanship and as interesting items to show off. What is particularly noteworthy here, is that the miniature books Arrietty owns (“borrowed” from the humans in the house at some point or other, we surmise) are all by the Glasgow firm David Bryce and Sons, a celebrated and prolific publisher of miniature books in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Bryce worked with printers at Glasgow and Oxford University Presses and he was, by all accounts, particularly good at marketing and promoting his miniature books, which became rather popular, many of them with very large print runs.7 Bryce’s miniature Bible, produced via photo-lithography, is particularly well known. However, Arrietty’s library seems to have consisted mainly of “secular” texts8 in Bryce’s “thumb” series, which were printed by letter press and were slightly larger than the later ones that relied on photo reduction9. Let’s look at Arrietty’s books one-by-one, alongside photos of the real miniature books (where available) from the National Library of Scotland’s amazing collection:

“Bryce's Tom Thumb Gazetteer of the World, including the last census”

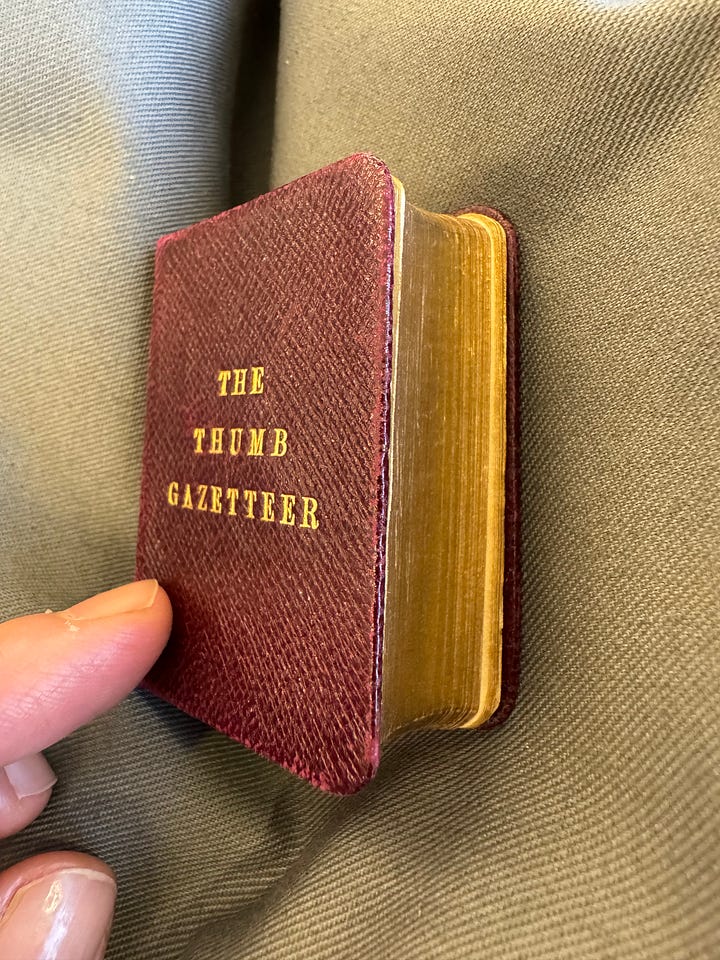

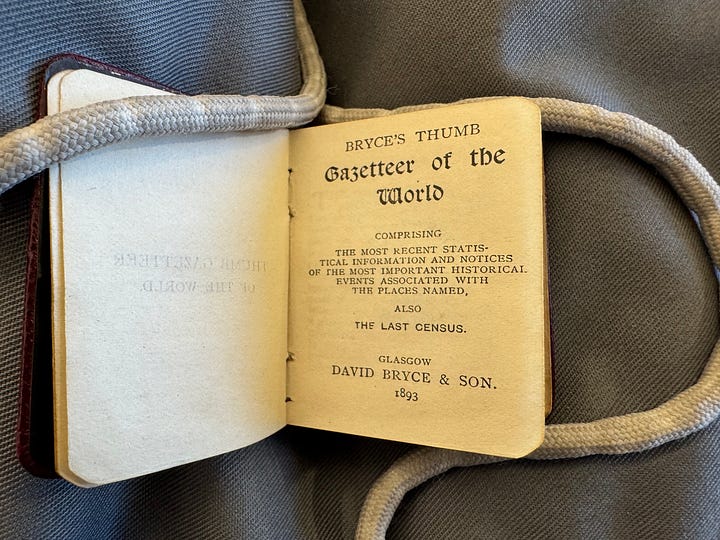

As shown in Figure 2, this 1893 book’s full title is: Bryce’s Thumb Gazetteer of the World, comprising the most recent statistical information and notices of the most important historical events associated with the places named, also the last census. It measures 2 ¼ by 1 ¾ inches (57mms x 44mms).10

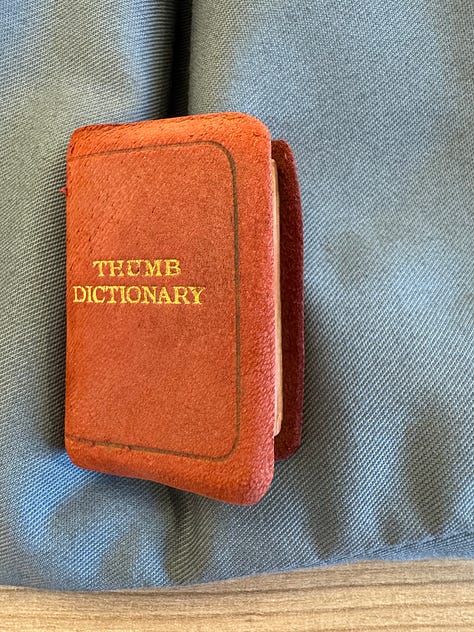

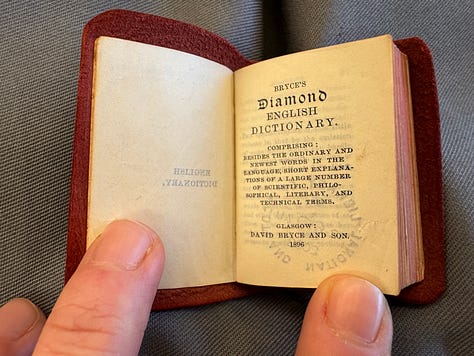

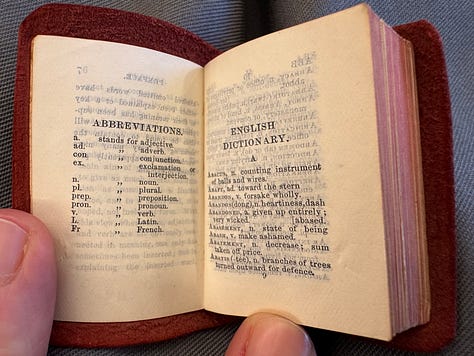

“Bryce's Tom Thumb Dictionary, with short explanations of scientific, philosophical, literary, and technical terms”

Now for this one, we have two possible candidates:

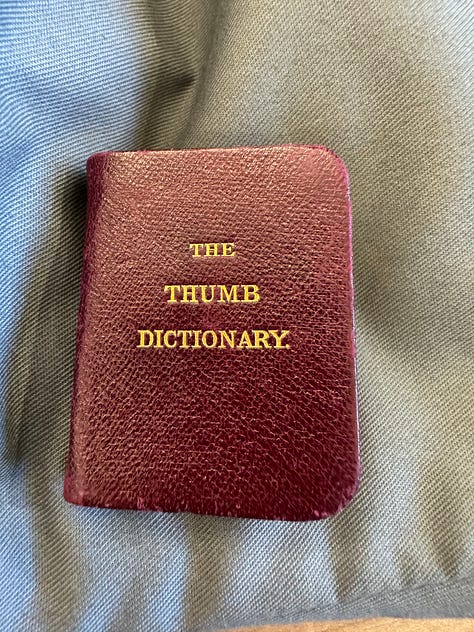

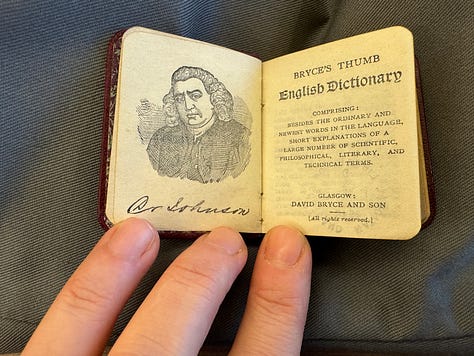

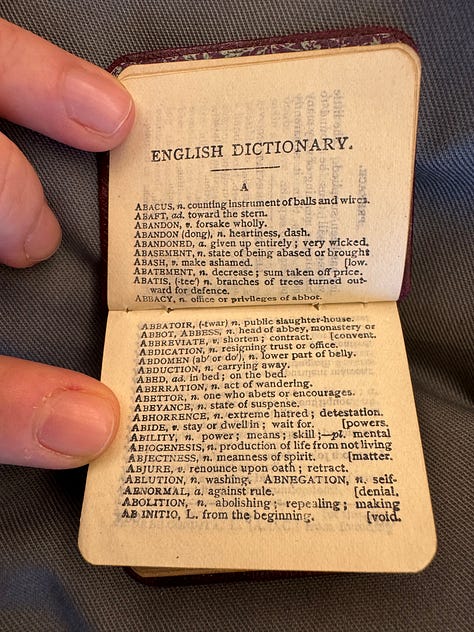

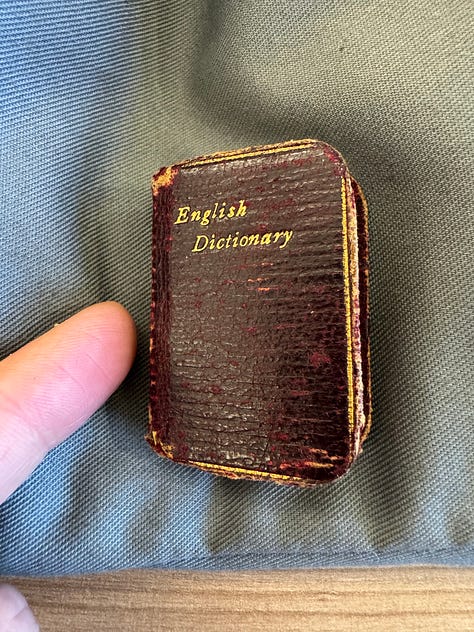

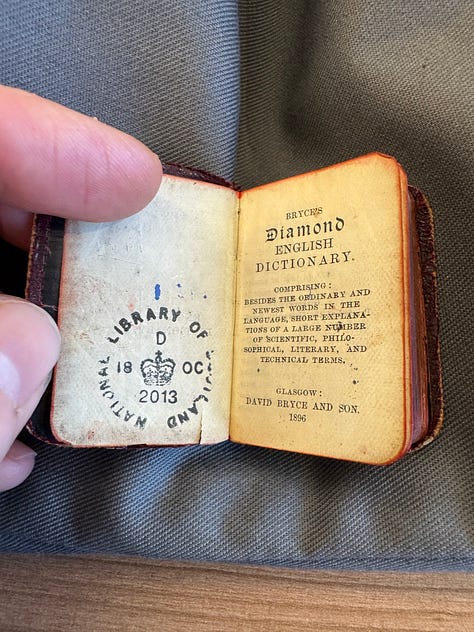

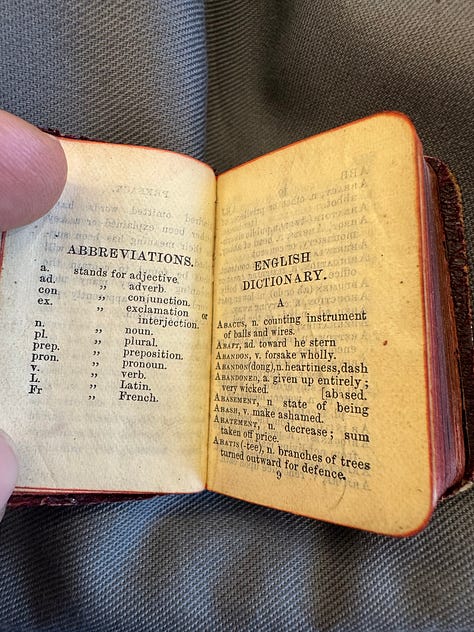

Bryce’s Thumb English Dictionary, comprising, besides the newest and ordinary words in the language, short explanations of a large number of Scientific, Philosophical and Literary terms (but notice that the narrator’s voice in The Borrowers adds “technical terms” too). It was published in 1888 (though it was on the market for a number of subsequent years)11 and measures 2 ½ by 1 ¾ inches (63mms x 44mms).12 Famously, the Dictionary includes a portrait of renowned lexicographer Samuel Johnson (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Bryce's Thumb English Dictionary, National Library of Scotland (NLS, Special Collections (https://search.nls.uk/permalink/f/sbbkgr/44NLS_ALMA21481256000004341) Bryce's Diamond English dictionary : comprising besides the ordinary and newest works in the language, short explanations of a large number of scientific, philosophical, literary and technical terms. This one does include “technical terms” in its title, as detailed in The Borrowers, but it’s not part of the “Thumb” series proper, but rather part of the “Diamond” series. Still, the “thumb” title must have become generic after a while, one would assume. See, for instance, the 2nd example of this very same book from the NLS in Figure 4 below. It’s clearly the same book, labelled “Diamond” in its title page, but the cover of the 2nd example still says “Thumb Dictionary”. This book was published in 1896, and is smaller, measuring 1 ¾ by 1 ¼ inches.13 My instinct is that the Dictionary in Arrietty’s library is this “Diamond” one.

Bryce's Tom Thumb Edition of the Comedies of William Shakespeare, including a foreword on the author

Now, here things get complicated. As far as I can ascertain, there is no Bryce’s Thumb edition of Shakespeare’s comedies. The celebrated Bryce endeavour involving Shakespeare was the “Helen Terry” series, dedicated to the “grand dame” of English theatre who “dominated the English stage in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras”.14 However, this was a 40-volume edition, with Shakespeare’s plays printed in individual tiny books, sometimes sold with a miniature revolving wooden bookcase. There was no single volume with all of Shakespeare’s comedies printed by Bryce. There was, however, a very early 20th-century (1903) Oxford Miniature edition of The Comedies of Shakespeare, one of three volumes, the other two collecting the Tragedies and Histories. I have only seen those for sale occasionally, as in this example. These are macrominiatures as they exceed 3 inches in height. Still, I think that examples such as these represent the sort of book Arrietty’s library included, and that is has been labelled as a “Bryce’s Tom Thumb Edition” because of the ubiquity of Bryce miniature books at the turn of the 20th century.

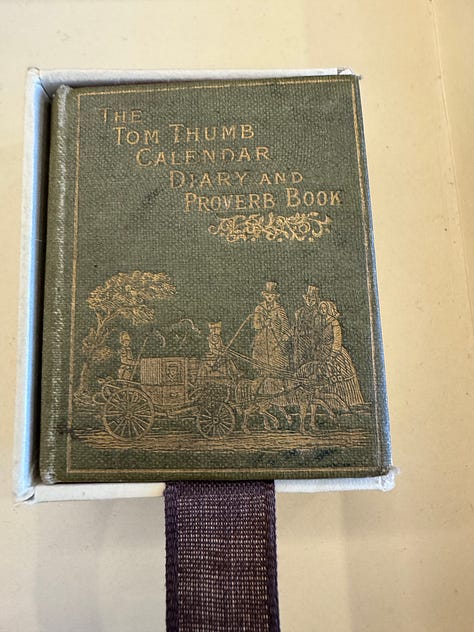

Bryce's Tom Thumb Diary and Proverb Book

This is the most important of the lot, as we realise later in this book (and in other instalments of the Borrowers series), that this is the book Arrietty used as a diary.

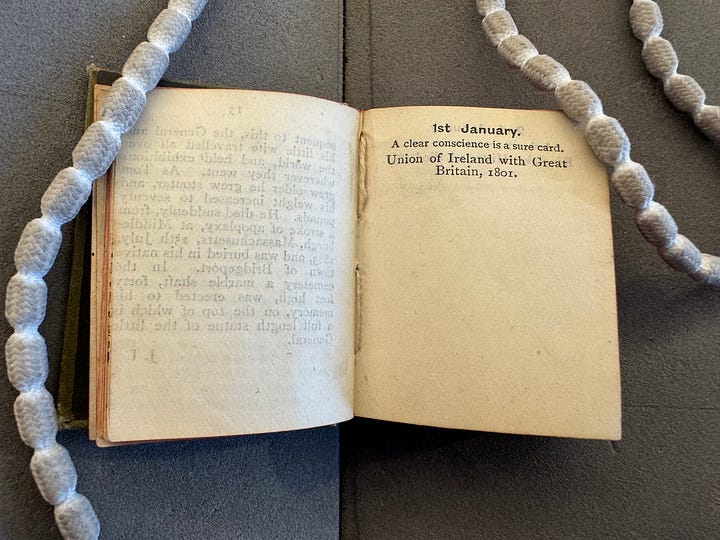

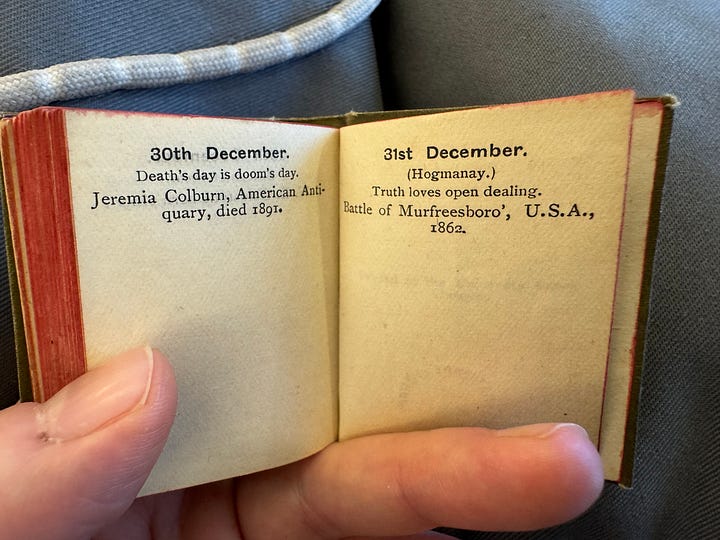

The full title of this 1893 book is Tom Thumb’s Calendar, Diary and Proverb Book.15 It measures 2 ¼ by 1 ½ inches (57mm x 40mm) and for each day of the year it offers a proverb and some event of note that happened on that date (see, for example, entries for 1st January and 31st December in Figure 5 above). It also contains a preface with a selective history of dwarfs from ancient to modern times, mostly focusing on the life story of American circus performer with dwarfism Charles Sherwood Stratton (1838-1883), better known by his stage name, “General Tom Thumb”, inspired, of course, by the English folk character of the same name.16 The cover of the book reproduces its engraved frontispiece: General Tom Thumb in his miniature carriage driven through London.

It was not unusual for miniature books to include introductions or prefaces or other relevant “front matter”, but the choice of this one is particularly interesting: a little book, with a prefatory text about a small person, and a cover and frontispiece to match. But in Arrietty’s hands, this question of small scale becomes more complex. As the narrator’s voice assures us: “Arrietty was not a stupid girl. She knew that horses could not be as small as mice”. I am not sure that the little horses pulling General Tom Thumb’s carriage (as represented on this book’s cover and frontispiece) are actually the size of mice - they cannot be reasonably described as ponies, I don’t think (too short for that?) but they are, perhaps, the size of a cat or dog. Still, the point here is that Arrietty realises that the small size of the horses is exaggerated to emphasize General Tom Thumb’s smallness. She knows mice and has a clear sense of their size - she’s encountered them many times around her home under the floorboards. She must also have a sense of how enormous (for Borrowers!) horses are: the big house in the recesses of which her family lives is a wealthy one, and horse-drawn carriages are not an unusual sight (see, for example, Chapter 19). Arrietty must have seen them through the grating by the kitchen close to her underground home.

Still, we are told, Arrietty “did not realize that Tom Thumb, nearly two feet high, would seem a giant to a Borrower”. So, Arrietty doesn’t quite realise that a human that seems extremely small to other humans (General Tom Thumb) would still be huge in relation to herself and her parents (who are the only Borrowers she has ever known at that point). If a human with dwarfism is the most extreme example of smallness the human experience can account for, what would be a human reaction to a Borrower? And how could Arrietty conceive of the actual, gigantic size of a “human bean”? All of these questions, of course, explode onto the page the moment Arrietty encounters the Boy, whom she first perceives as a giant Eye. This tiny fragment of commentary on the (real) miniature book Arrietty owns, therefore, and its subject matter, begins to open up one of the key themes the book is set to explore as the story unfolds.

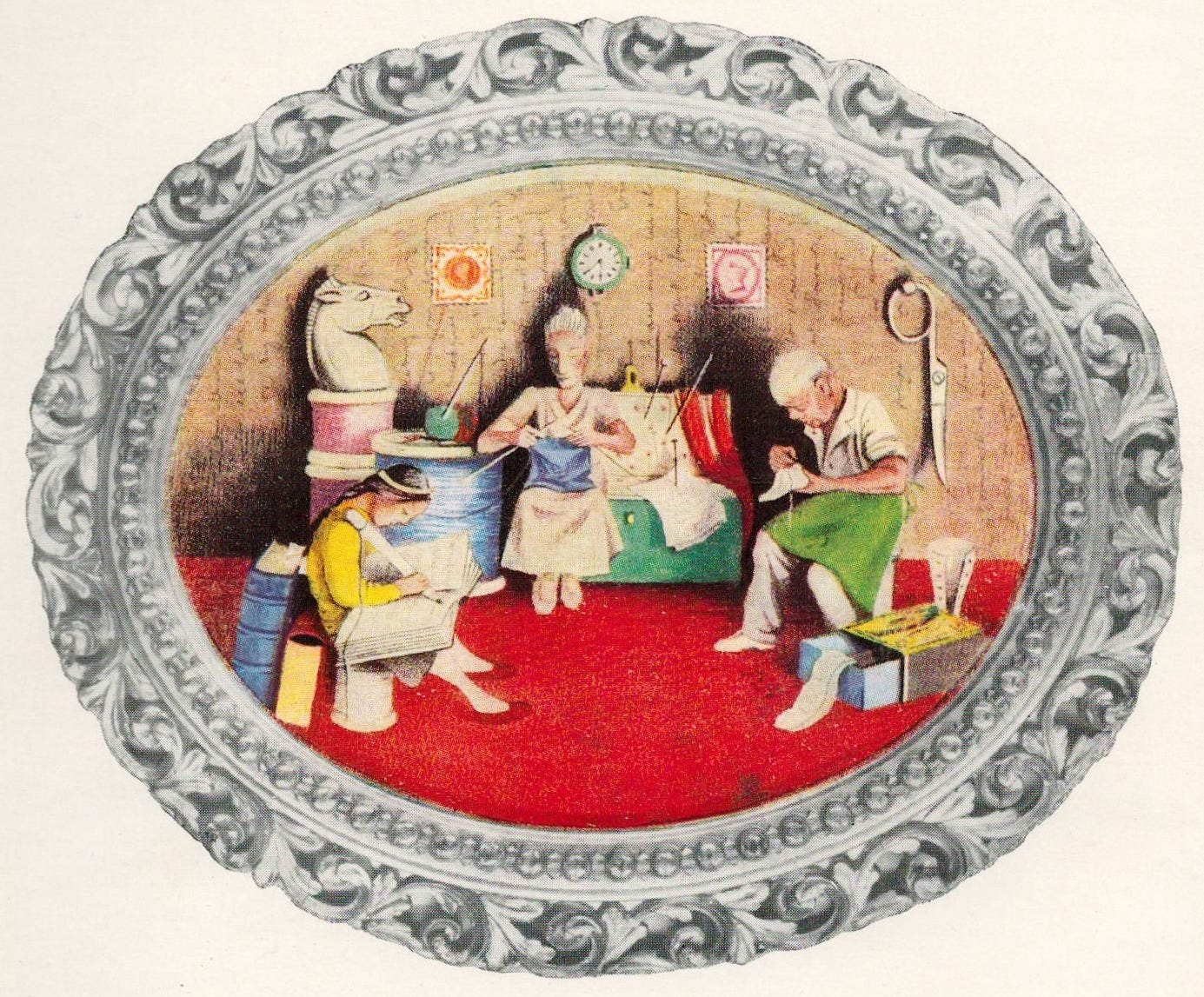

Tom Thumb’s Calendar, Diary and Proverb Book is also interesting because of the book’s own size in relation to Arrietty. We have already been told that the Bryce miniature books Arrietty owns are too large for her, “the size of very large church Bibles”. When we first watch Arrietty writing in her diary we find out that she has to “heave” the book on her knees. See also the illustration of Arrietty writing in her diary in Figure 1, which depicts quite well the idea that the diary is too big for her, as well as the illustration in Figure 6, in which Arrietty is resting an enormous book on her knees. Still, that’s all Arrietty has as writing material, and so she uses it. In fact, Tom Thumb’s Calendar, Diary and Proverb Book is a really neat idea as a diary for a little person, as it was meant to be used as a calendar/note-taking tool anyway, and, though still limited in its scope, it can serve Arrietty for a long time:

She allowed herself (when she did remember to write) one little line on each page because she would never—of this she was sure—have another diary, and if she could get twenty lines on each page the diary would last her twenty years.

This diary becomes part of the “framing” of The Borrowers, giving the reader clues as to what might have happened to Arrietty and her family after the dramatic end of the story (no spoilers!) In this novel, the speculation on whether the Borrowers survived and went on to live elsewhere is fuelled by the discovery of the diary (though its reliability is questioned). In addition, in some of the sequels, the diary is also at the heart of the question of the veracity of the Borrowers’ adventures (I hope to return to this topic at some point!)

Hymns and 60s Hits in The Doll People

The Doll People is the first of a series of four books and one picturebook. They are written by Ann M. Martin and Laura Godwin, and illustrated by Brian Selznick. The books follow the adventures of Annabelle Doll, a 19th-century porcelain doll who lives in the US, in an antique dollhouse with her extended family (though the dolls and dollhouse were ordered from Britain). Their current owner is Kate Palmer, though the dollhouse and dolls have been in the family for a long time, passed down the generations from mothers to daughters. Later on in the story, another family of modern, plastic dolls, the Funcrafts (and their house), arrives as a present for Kate’s younger sister, Nora.

The Doll People is set up as a mystery story. Right from the beginning, we hear that a member of Annabelle’s family, Auntie Sarah, disappeared forty-five years ago and is still missing. Part of the plot involves unravelling the mystery and finding Auntie Sarah. And one of the crucial items that Auntie Sarah has left behind, and that Annabelle discovers and so starts her sleuthing, is a written document: Auntie Sarah’s diary, which must be a miniature book.

The miniature books mentioned in The Doll People may not be described with too much verisimilitude, or in enough detail, to help me identify real-world examples, but they are part of the setting of the story and important to the plot. The first time we hear of their existence is in Chapter 1, when all of Annabelle’s family find the front of the dollhouse closed, which means they can have freedom and privacy to move.17 They decide to use that time for what is clearly a family favourite pastime: gather around their piano for a sing-along (like a good Victorian family!). But the songbooks they sing from are not quite the combination one would expect:

The Dolls had gathered around the piano in the parlor. Uncle Doll propped two songbooks in front of him. One was a book of hymns. It had come from England a hundred years earlier with the Dolls and the house and the furniture. The other book had been purchased by Mrs. Palmer, Kate’s mother, when she was a young girl and the dollhouse had been hers. On the cover of the book was a rainbow. Written across the yellow band of the rainbow were the words GREAT HITS OF THE SIXTIES.

“Let’s sing ‘Natural Woman,’” Annabelle had suggested.

“Yuck,” said Bobby.

“Okay, then ‘Respect,’” said Annabelle.

“R-E-S-P-E-C-T!” sang Bobby.

“Sockittome, sockittome, sockittome, sockittome!” Annabelle chimed in.

“How about a quieter song?” suggested Nanny.

The Dolls had sung song after song while Uncle Doll played the piano. […] The Dolls ended the singalong after two choruses of "Bringing in the Sheaves” from the hymnbook. And then their free time began. Annabelle knew exactly what she was going to do. She wanted to examine the books in the library. And she wanted to do it privately.

The Doll People, Chapter 1

From the two miniature books mentioned here, the book of hymns is the one that can definitely point to a real-world edition, of which there were many. As Bondy notes, towards the end of the 19th century “Hymns Ancient and Modern were published in huge numbers and many of the miniature editions have survived”,18 including an edition by William Clowes & Sons in London. The hymn book Annabelle’s family use could be one of many different editions. But I think that the Great Hits of the Sixties miniature book, with a rainbow on its cover, is probably an invention for this particular story (to create a particularly humours incongruence with a religious/devotional text). Unless anyone knows of a real-world example, perhaps a miniature book made for dollhouses? I’d be grateful for any ideas!

Still, the other important point in the extract above, is that this dollhouse has a library! Annabelle suspects that there is some clue connected to Auntie Sarah there, so she visits the library to investigate. To her disappointment, she mostly finds many “pretend” books, but also some real ones, and a big surprise:

Annabelle knew that most of the books on the shelves were not real. They were simply flat blocks painted [in] bright colors, with book titles written on one side in gold ink. […]

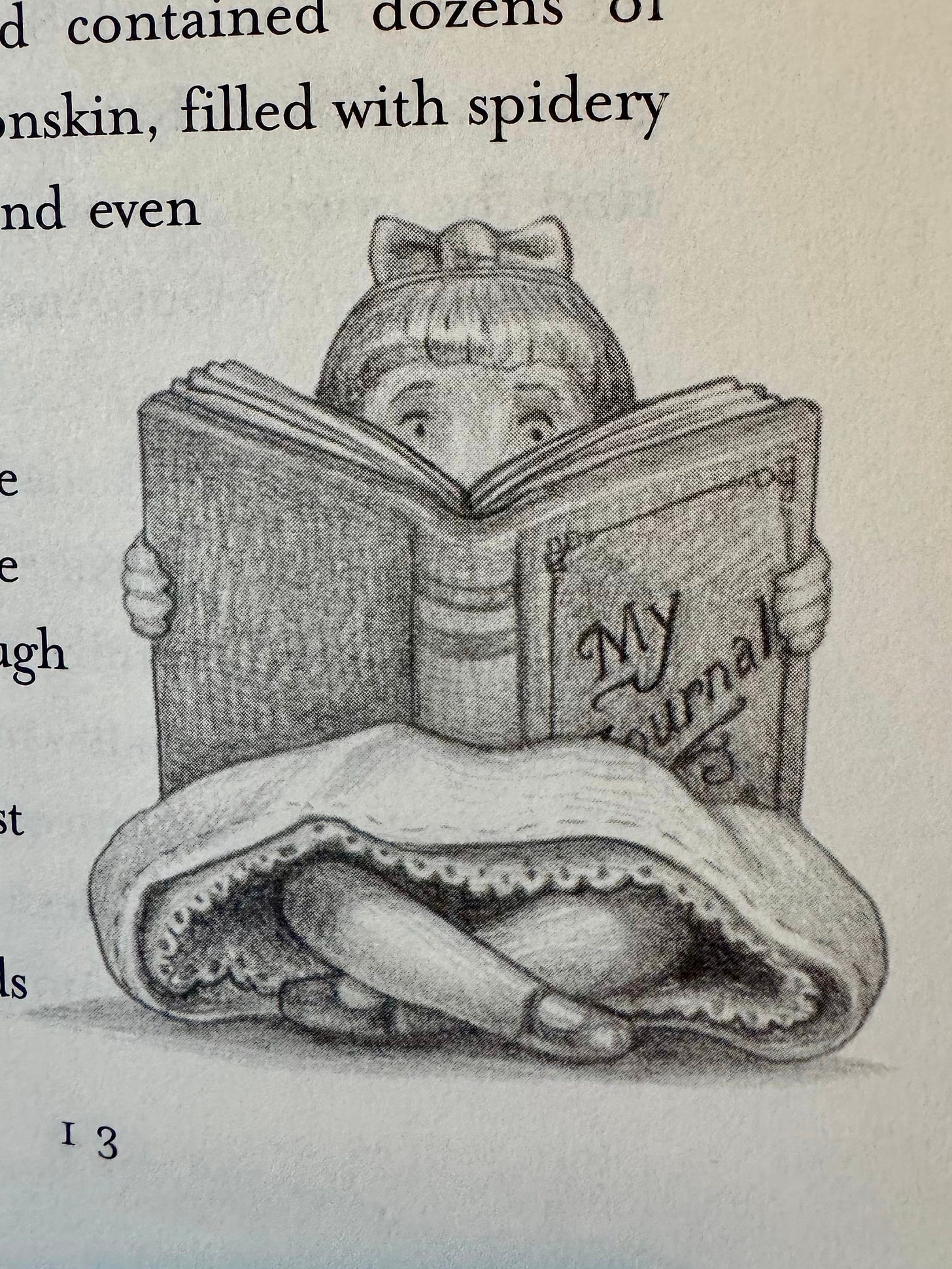

She started by removing the books from the shelves, one by one. Presently she discovered that some of the books were attached to one another. She could remove a whole block of books at once. […] Then she discovered that some of the books were, in fact, real, like the songbooks. She could open their covers and inside were a few pages with crowded writing: Classics of Modern Poetry, Oliver Twist. Annabelle read the twenty-page story about the little boy named Oliver with great interest. Eagerly, she pulled out every book from the shelves. But the others were pretend. She checked for secret compartments. Nothing. She stood on a stool and tackled the next shelf. Only pretend books. She stood on tiptoe and reached for the shelf above. And that was where she found Auntie Sarah’s journal.

The idea of “pretend” books, look to make like volumes stacked on library shelves, but really just flat blocks painted to look like book spines, some of which are stuck to each other and can be removed as blocks, is interesting in itself. If miniature books are a serious adult collecting pursuit, with exacting expectations for craftsmanship and proportion, the dollhouse library seems to be a mockery of this (and of the supposed “simulation” of a real house in small scale) but taking shortcuts and caring more for appearances rather than substance.19 For the humans owning the dolls and dollhouse, this is, of course, a shortcut worth taking to create the illusion of a miniature house with all expected contents.20 But when it comes to dolls that are alive and live their lives in such edifices, then fake books are no good at all. Even the other books Annabelle discovers here are not really collectors’ items: I can’t find a mention of important tiny editions of Oliver Twist in the usual miniature book bibliographies, and the fact that the one Annabelle reads is only 20 pages long points to another type of “pretend” miniature book: an abridged version made specially for dollhouses, usually in pretty large font. As for the Classics of Modern Poetry, I think this is also a made up miniature book for the purposes of the story (but do correct me if you know otherwise!)

Still, the most important “book” here, as is the case with The Borrowers, is a diary. We don’t get much of a description of the book Auntie Sarah has used, other than that it’s dark green and it’s titled (in gold writing) My Journal. On the first page Auntie Sarah has written: “The Private Diary of Sarah Doll, May 1955”. The book contains “dozens of pages as thin as onionskin, filled with spidery black handwriting and even some drawings”. Is this another “fake” book left blank that Auntie Sarah decided to turn into a real document? Or is it a “simulation” of a blank Journal in miniature? Again, I can’t find any mention of such a real-world miniature book (unlike Arrietty’s diary) so my assumption is that it’s there to serve the story. Indeed, Annabelle finds enough clues in the diary to realise that Auntie Sarah was getting bored of the monotonous life of the dollhouse (just like Arrietty!) and had started exploring the human house, fulfilling her desire to become and naturalist and study spiders (all good Victorian ambitions, especially for a forward-thinking fin-de-siècle woman).

Miniature Books and Women’s Writing

The presence of miniature books in both The Borrowers and The Doll People may be read as an element of whimsy, and part of the celebration of all things tiny that such children’s fantasies seem to privilege. Still, they tell us a lot of things:

They testify to the popularity of miniature books at the turn of the 20th century in upper middle-class households in Britain and the US, so much so that a whole “library” of such books can be formed by “borrowing” and go unnoticed, or be bought specially for a dollhouse.

They are part of the mix of materialities that little people (both imaginary small humans and small dolls-come-to-life) live around, a combination of the detritus of human everyday existence, and bespoke small things made to showcase craftsmanship or to allow young children (mostly girls) to play-act “domesticity” by running a tiny simulation of a house.21

Most importantly for the plots of both novels, however, these miniature books open up avenues to education (Arrietty learns to read from them, and Annabelle finds fascinating stories, as well as her aunt’s naturalist notes), and allow women’s writing to flourish: as Harriet Blodgett notes, “along with letters, diaries have been women’s most common form of writing in English over the centuries”.22 As we have seen, Arrietty’s and Auntie Sarah’s diaries in these two books play different roles: the former becomes part of the “evidence” of the existence of the Borrowers, while the latter allows Annabelle to become herself an explorer and find her daring Aunt. Both diaries offer important clues associated with the act of writing things down.

I am leaving things here for now, but I hope to return to a number of different topics and themes only touched upon in this piece. Watch this space!

Anne C. Bromer and Julian I. Edison, Miniature Books: 4,000 Years of Tiny Treasures (Abrams, 2007), pp. 11-12.

‘Nutshell’, Oxford English Dictionary Online <www.oed.com/view/Entry/129343>

Pliny, Natural History, Book VII, Chapter 21. Available at: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D7%3Achapter%3D21

Bromer and Edison, p. 114.

We are not given exact measurements until the second book in the series, but we’re looking at the standard 6 inches height here for Pod’s height. I hinted at the 6-inches height as a general expectation in fantasies with little people in my previous piece - I will write a separate piece to explain all of this, I promise!

The setting of The Borrowers in terms time is a complicated matter, worthy of an entire separate piece! I will try to have a go at that at some point!

See Louis W. Bondy, Miniature Books: Their History from the Beginnings to the Present Day (Sheppard Press, 1981), pp. 103-116.

The majority of miniature books across the ages fall into two categories: religious texts (Bibles, Psalms, etc., including non-Christian texts) and classical texts (Greek and Roman literature and philosophy). Arrietty’s library is more representative of the diversification of subject-matters in miniature books in the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

See Bondy, p. 104; also Michael Garbett, An Illustrated Bibliography of Miniature Books Published by David Bryce and Son (The Final Score, 2011), p. 13.

See Garbett, p. 13.

See Bondy, p. 104.

See Garbett, p. 14.

See Bondy, p. 108.

See Bromer and Edison, p. 50.

Though it was also sold as Bryce’s Tom Thumb Diary and Proverb Book (see Garbett, p. 15), which seems closer to the title as given in The Borrowers.

Obviously, Tom Thumb (either the folklore character, or the 19th-century performer) is attached to the title of this miniature volume in the “thumb” series, though the term “thumb” to refer to miniature books (e.g. “thumb” Bibles) was common from much earlier than Bryce’s books. The idea of using a “thumb” (roughly an inch, i.e. the width of an adult thumb) as a unit of measurement is much older still.

In this series, some dolls have taken an “oath” (“The Doll Code of Honor”) and are alive, but can revert to “Doll State” or even “Permanent Doll State” if they are seen moving/talking by humans, thus endangering “dollkind”.

Bondy, p. 131.

The idea of dollhouse items not “fitting” with the size of miniature people in children’s fantasy, or being “fake” and therefore useless, is one I shall return to, because it comes up again and again.

This idea of illusion is also important. Even elaborate, costly, world-renowned dolls houses take such shortcuts. A good example is the beautifully intricate miniature library in Queen Mary's Dolls' House, which does include 100s of minuscule volumes, made specially (again, a topic I shall return to at some point), but which still contains “241 blank books bound in red or blue card, created to fill up the shelves” (Elizabeth Clark Ashby, The Miniature Library of Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House, Royal Collection Trust, 2024, p. 25).

On this last point see Wei-Ning Chen’s fascinating 2014 thesis “To the Dolls’ House: Children’s Reading and Playing in Victorian and Edwardian England”.

Harriet Blodgett, “diaries (journals)”, in The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English, edited by Lorna Sage (Cambridge University Press), p. 187.

How is the miniature Alice book stored? I'd worry about sneezing it away.

It occurs to me that the most miniature of people are the Whos in Whoville, whose entire planet is smaller than a speck of dust!