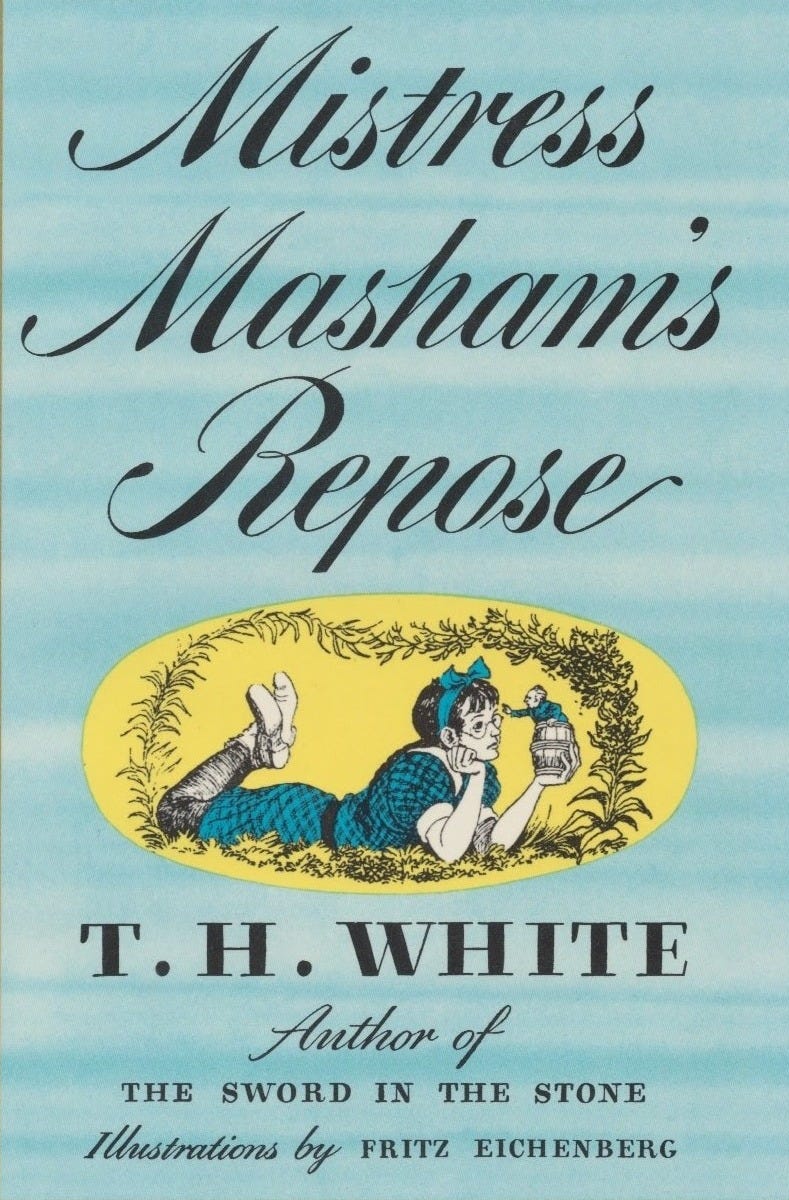

T.H. White is probably best known for his series of Arthurian novels, published together as The Once and Future King, though the most popular book in the series remains the first one, The Sword in the Stone (1938). But in 1946, he published his “little people” story, Mistress Masham's Repose, which was destined to launch a new sub-genre within miniature fantasy. In this book, orphaned Maria is (in name only) the heiress of a derelict family estate, the Palace of Malplaquet, and its extensive grounds. In reality, she is tyrannised by her guardian and governess, and her only friends are the kind cook and an absent-minded retired professor. Love-starved and full of a vivid imagination, Maria is ecstatic to discover that a tribe of little people live in the inaccessible island in the middle of an ornamental lake in a corner of the estate (the “Repose” of the title). She soon finds out that this is a colony of Lilliputians, actual Lilliputians as encountered and described by Lemuel Gulliver in his Travels (Jonathan Swift, 1726). The sub-genre this novel gave rise to, therefore, is the “children encountering Lilliputians” storyline1. Other examples include:

Castaways in Lilliput, by Henry Winterfeld (1961)

The Antelope series by Willis Hall, based on the Granada TV series (The Return of the Antelope, 1985; The Antelope Company Ashore, 1986; The Antelope Company At Large, 1987)

Andrew Dalton’s Malplaquet Trilogy (The Temples of Malplaquet, 2005; The Lost People of Malplaquet, 2007; The New Empire of Malplaquet, 2009)

Lilliput, by Sam Gayton (2013)

In these books, either children find their way to the island of Lilliput, just like Lemuel Gulliver did, or, most often, they somehow encounter Lilliputians who have made their way to Britain in one way or another.

The Lilliputian back-story, and the discourse of slavery

In T.H. White’s novel, the Lilliputians have found themselves in Malplaquet because of Gulliver’s indiscretion and lack of understanding of humanity’s worst instincts. As the People2 tell Maria, Gulliver “had made no Efforts to conceal our Whereabouts from the greater World” and had told the captain that took him back home, Captain John Biddel, all about his adventures in Lilliput, showing him the evidence of his encounter with the Lilliputians he had taken with him: miniature livestock. All of this agrees perfectly with the closing paragraphs of Part I of Gulliver’s Travels, “A Voyage to Lilliput”. When Gulliver escapes from Blefuscu (the island next to Lilliput, also populated by tiny people) he sees and hails a ship:

The vessel was an English merchantman, returning from Japan by the North and South seas; the captain, Mr. John Biddel, of Deptford, a very civil man, and an excellent sailor.

[…] This gentleman treated me with kindness, and desired I would let him know what place I came from last, and whither I was bound; which I did in a few words, but he thought I was raving, and that the dangers I underwent had disturbed my head; whereupon I took my black cattle and sheep out of my pocket, which, after great astonishment, clearly convinced him of my veracity. I then showed him the gold given me by the emperor of Blefuscu, together with his majesty’s picture at full length, and some other rarities of that country. I gave him two purses of two hundreds sprugs3 each, and promised, when we arrived in England, to make him a present of a cow and a sheep big with young.

[…] The rest of my cattle I got safe ashore, and set them a-grazing in a bowling-green at Greenwich, where the fineness of the grass made them feed very heartily, though I had always feared the contrary: neither could I possibly have preserved them in so long a voyage, if the captain had not allowed me some of his best biscuit, which, rubbed to powder, and mingled with water, was their constant food. The short time I continued in England, I made a considerable profit by showing my cattle to many persons of quality and others: and before I began my second voyage, I sold them for six hundred pounds. Since my last return I find the breed is considerably increased, especially the sheep, which I hope will prove much to the advantage of the woollen manufacture, by the fineness of the fleeces.

Gulliver’s Travels, Part I, Chapter VIII

The backstory of the events in Mistress Masham’s Repose is that Captain Biddel saw immediately the economic potential of the miniature cattle and sheep, and returned to the latitude where he picked up Gulliver, found Lilliput, and not only raided livestock, but also abducted People from both Lilliput and Blefuscu. The two nations had actually been at war during Gulliver’s visit, and they’re portrayed in this novel as exhausted from their long conflict when Captain Biddel descended upon them to finish them off. As the Lilliputian Schoolmaster tells Maria:

to him our broken and distrackted People were Creatures not possessed of human Rights, nor shelter'd by the Laws of Nations. Our Cattle were for his Profit, because we could not defend them; our very Persons were an Object of Cupidity, for he had determined to show us in his native Land, as Puppet Shews and Mimes. […] Lilliput, Madam, and Blefuscu, ceased at that ill-fated Epocha from their Existence among the Nations of Antiquity.

Mistress Masham’s Repose, Chapter VII

The instinct of Captain Biddel as described here is clearly exploitative and is deliberately paralleled with colonial practices and “justifications”. He and his men come to Lilliput and Blefuscu as “Pyratts”, “in Search of Slaves” (see first panel of Figure 1), and the handful of men and women they capture are transported to Britain “in an insanitary Box”, crammed together and fed “a Diet of Ship’s Biscuit crumbled in Water”, which is exactly what Gulliver had fed his miniature cattle aboard Biddel’s ship (see quotation above). This transportation in inhumane conditions, treated like animals, brings to mind the most horrible circumstances of the “Middle Passage”, the second stage of the slave trade triangle, in which enslaved peoples from Africa were forcibly removed and transported to the Americas, crammed together in tight spaces, rarely allowed above deck, starved, and in an environment full of disease.

In Mistress Masham’s Repose, once the People (who are, ostensibly, enslaved) have been transported to Britain, they made to perform in public (see second panel of Figure 1): either play music with specially commissioned musical instruments at their scale, or display the “ancient Skills of Lilliput, such as Leaping and Creaping, or Dancing upon the Strait Rope”. On top of that, the English language is “ruthlessly impress’d upon them”, they are taught to cry “God save the King!”, and any disobedience or misdemeanours are punished by “Flogging with a Sprig of Heather”. The Schoolmaster concludes that the enslaved people had “no other Prospect of Amelioration, than the Amelioration of the Grave”. Once more, many of these circumstances and predicaments bring to mind enslaved and colonised peoples, forced work, imposed language change, and so on.

But the People eventually manage to escape4 (see third panel of Figure 1), and that happens when Captain Biddel has been “summon’d to the Palace of Malplaquet, in order to demonstrate his Puppets before the Household of the reigning Duke”. Note the use of the word “Puppets” here - once more, an objectification as part of subjugation. But eventually the escapees make their way to the lake island and become the ancestors of the populous secret community Maria sees.

Historical manners and materialities

In terms of timescales, the People escape at some point in the very early 18th century (if Gulliver travels to Lilliput in 1701, according to the Travels, and then Captain Biddel arrives “after a Lapse of seventeen Moons” after Gulliver’s return, we’re looking at around 1702-1703), and Maria meets them at around the time of the novel’s publication in 1946 (we’re definitely post-war, as Clement Attlee is the prime minister in Chapter XXVIII). So nearly 250 years have elapsed since the enslaved People escape and set up their new colony at Malplaquet.

This time discrepancy gives the novel the opportunity to present the People as having an old-fashioned, historical materiality compared to Maria’s 20th-century context, and this is also the case with their manners and linguistic register. The clothes that Captain Biddel had made for them are roughly right for the early 18th-century: “skirted coats of blue silk, white pantaloons, white stockings, buckled shoes, three-cornered hats, and ladies’ dresses”. Their musical endeavours are also of that period: the music they produce comes from “a queer, eighteenth-century band, with flutes, violins, and drums”, and later on we also find out that their orchestra included “a miniature harpsichord”.5 What is more, their manners are equally old-fashioned (perhaps not strictly 18th-century, but indicative of “old times”): the Lilliputians are prone to drop curtsies and to “making a leg” (the men show their respect to Maria by “put[ting] forward their left feet, placing the other foot behind at right angles, and […] bowing to her”). Their speech is also rendered in an old-fashioned way, with (what seems to our modern sensibilities) odd capitalizations of nouns (see the block quotation above). This is turned into a very funny moment when Maria responds to one of the People’s very formal addresses by saying that she would “endeavor to merit their Confidence and Esteem—goodness, she thought, I have begun to talk in capitals too”! As Maria and the People become more familiar with each other (and their power dynamics change a bit too), the latter’s linguistic register changes slightly, in a very appropriate 18th-century fashion:

She noticed that they were no longer calling her “Y’r Honour,” but “Miss,” which was the proper eighteenth-century address for girls, and this made her feel pleased. She did not know why.

To please Maria when she visits them “officially” for the first time, the People lay out bunting with an interesting version of the Union Jack:

In the center the Union Flag was flown, which she was able to recognize as the standard of England, although the red stripes were missing on the diagonals. The real Union Jack did not come in until long after Hogarth’s time, although Maria did not know this fact.

This sort of makes sense: the UK’s national flag (Union Jack or Union Flag) as we know it today was standardized in 1801, after the 1800 Act of Union, which created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and (then) Ireland. By that point, the flag was mostly as we know it today, but lacked the red saltire on white (counter-changed with the cross of St Andrew) to symbolize Ireland6. This, indeed, agrees with the lack of “red stripes missing on the diagonals” as per the quotation above. What puzzles me is the time reference in this quotation, that the “real” Union Jack did not come in “until long after Hogarth’s time”. I’d love to hear readers’ thoughts on this, but I think this probably refers to Hogarth’s 1750 painting The March of the Guards to Finchley, perhaps one of the better-known British “masterpieces” that includes the Union Flag, which, indeed, lacks the red saltire on white. If so, then the timeline works too: it makes sense that the Lilliputians will have the older version of the Union Flag, which, indeed, didn’t become standardised as the version we know today until 51 years after Hogarth’s painting, and nearly 100 years after the Lilliputians arrived in Malplaquet.

The 18th-century context also works well for the tune the Lilliputian band plays during Maria’s first “official” visit: “The British Grenadiers”. This is a British Army marching tune that goes back to 1704 or 1705,7 so chiming quite nicely with the time of the People’s arrival at Malplaquet. However, the tune they play next, “A Right Little, Tight Little Island”, takes us to another time, nearly 100 years later. This patriotic song, properly titled “The Snug Little Island”, was first composed and performed in 1797, and so alludes to the Napoleonic era.8 The Napoleonic context, with Nelson as a protagonist from a British perspective, comes back as a significant point of reference later on in the novel, when the People muster their army to save Maria, who has been locked away by her horrible nanny and guardian (the Vicar). Here is how the army is described:

There were the infantry in mouseskins standing at attention, their officers, in beetle breastplates, standing three paces to the front, with swords unsheathed. There were the cavalry, with the Admiral at their head—waving his saber and dressed in one of the ancient dresses of Captain John Biddel, so that he looked like Nelson. As with all Admirals, he sat his rat badly. There also were the archers, with their left feet forward as if they had been at Agincourt. Behind these, in orderly ranks, stood the Mother's Union, the Ladies Loo Club, the Bluestockings, and other female organizations, all singing lustily and waving banners, which stated: "Votes for Maria," "Down with Miss Brown," "No Algebra without Representation," "Lilliput and Liberty," "No Popery" (this was for the Vicar), or "Schoolmasters Never Shall Be Slaves." The A.D.C.'s were cantering up and down with messages; the bugles were blowing; the drummer boys were beating to quarters; the regimental standards were uncased; the band had changed over to “Malbroock s'en va-t-en guerre”; the swords and pikes and harpoons were flashing in the golden light; and, even as Miss Brown peeped, a flight of arrows was discharged against the window "as it had been snow." "Huzza!" cried the infantry. "Death or Glory," cried the cavalry. "The Admiral expects..." cried the Admiral, but when one of the A.D.C's had whispered to him behind his hand, he quickly changed it to the better phrasing: "Lilliput Expects That Every Man This Day Will Do His Duty."

Now, at this point I need to credit my excellent colleague Prof. Tony Pollard, who helped me disentangle the mishmash of military and naval references in this extract. Here are Tony’s notes:

Mouseskins is a take on bearskins. This might place them in the Napoleonic era when Napoleon's Imperial Guards wore similar - the British Guards adopted them after Waterloo (1815) almost as a battle honour.

Breastplates have a longer history and develop from the full armour worn in the medieval period. They were widely adopted as just breastplates (sometimes front and back) from the 16th century onwards (think Oliver Cromwell). They were also worn at Waterloo but again by Napoleon's troops - but only some of his cavalry regiments. The armour was known as the Cuirass and the troops Cuirassiers. Again the British adopted them after then - look up today's Life Guards.

the cavalry, with the Admiral at their head… he looked like Nelson - of course there is anomaly here with an Admiral leading cavalry, and Nelson providing a firm hook to the Napoleonic era. The only battle I can think of where an Admiral fought in a land battle was Flodden, 1513 (Thomas Howard, Lord High Admiral of England).

Archers are well abandoned by the Napoleonic era; and Agincourt was fought in 1415.

A.D.C. is Aide-De-Camp (assistant to senior officer or general).

Beating to quarters is a naval term - Master and Commander.

Pikes and harpoons - A real mishmash - pikes dominate the battlefield in the 16 and first half of 17th century (Oliver Cromwell again). Harpoons are obviously maritime, and not military.

“Lilliput Expects That Every Man This Day Will Do His Duty” - Another reference to Nelson - an adaptation of the message he put out before the Battle of Trafalgar (“England expects that every man will do his duty”).

So what we have here (and in the reference to “The Snug Little Island” above) is an accumulation of clues that tend to point towards the Napoleonic era (1799-1815), Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), as well as the Battle of Waterloo at 1815 (the latter marks the end of the Napoleonic wars).

Why would the Lilliputians be emulating an army of the Napoleonic era? Their engagement with British history and culture was in the very early 1700s, at which point they escaped and led their own independent lives until Maria found them in the mid-20th century. How come they are imitating/parodying Nelson and military practices of the Napoleonic period? This choice doesn’t make sense in terms of the internal, fictional history of the People, but does it make sense as a creative choice in other ways? Is T.H. White choosing a particularly well-known period of British patriotic fervour to show the People courageously fighting to save Maria, especially for a novel published (and set) just after World War II? Is there, perhaps, a dearth of good, wholesome moments of British patriotic pride in the previous century to make use of instead? Perhaps. Has this period been selected because it coincides with the beginning of the end of slavery in Britain,9 and therefore offering a corrective to the awful behaviour of Captain Biddel a century earlier? Or is it that the People evolve militarily and historically, but maybe at a much slower rate than their big people counterparts, and thus have only made it, materially/militarily, up to the Napoleonic era in nearly 250 years? I am genuinely still thinking about this and would be happy to hear any suggestions from readers! (I have a feeling I am missing something important…)

As one expects, of course, after many trials and tribulations Maria is rescued and, in turn, she helps rescue the People from the two baddies of the novel. She also regains control of her estate, which becomes the perfect, peaceful abode for the People for the foreseeable future.

There are all sorts of other fascinating themes and ideas in the novel, such as the ways the People have adapted to their natural environment, their establishment of a sort-of-utopian society, and Maria’s eventual understanding (mostly by getting things wrong and learning from her errors) that the People are independent beings with their own wills, lives, agency, and human rights, not toys to be played with and bossed around.

I shall be returning to this novel to explore material entanglements, ethical questions, and the ways it must have served as a key inspiration for Mary Norton’s The Borrowers and its sequels. For now, I am leaving you with the novel’s historical dimensions and it’s Swiftian resonances.

At least I don’t know of any earlier examples of this trope - if anyone does, please let me know!

Interestingly, Maria starts referring to them as “the People” early on in the novel, presumably an abbreviation of the “People of the Island” or the “People of Lilliput”, both terms also used in the novel. But, of course, the term “People” also raises all sorts of ethical and moral questions, as we shall see.

Lilliputian currency. A sprug is described in Gulliver’s Travels as “their greatest gold coin, about the bigness of a spangle”.

There are historical cases of runaway slaves, though often to great cost and danger.

There is a lot more to be said on how the Lilliputians’ materialities have evolved in their new natural environment, but I shall return to this in another post.

According to the Flag Institute, when Ireland achieved its independence as the Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland) in 1921, “changes to the Union Flag were discussed […] but no action ensued”.

See Hart, Ernest. 1918. “British Regimental Marches: Their History and Romance”, The Musical Quarterly, 4(4): 579-86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/737882.

Wheeler, Harold F. B. and Broadley, Alexander Meyrick. 1908. Napoleon and the Invasion of England: The Story of the Great Terror. London; New York: J. Lane. https://archive.org/details/cu31924024326724/page/n311/mode/2up.

The Slave Trade Act of 1807 abolished the slave trade while the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 was the beginning of the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire.

"Is there, perhaps, a dearth of good, wholesome moments of British patriotic pride in the previous century to make use of instead?" By no means! Lots of patriotic British military success from the appropriate period: Blenheim, say (Blenheim Palace, the real world model for Malplaquet, memorialises Churchill's triumph there) ... or indeed the Battle of Malplaquet itself: the larest battle in the 18th century. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Malplaquet

The Napoleonic touches are anachronistic, really, although could be explained away with in-story hypothesis: that the outside world had intruded on the island during 1815-20, and then abandoned the Lilliputians again.

I could add: I also wrote a Lilliputian novel, "Swiftly" (2008). In mine Lilliputians are set to work inside "Difference Engine" machines, briging forward the computing revolution. Although that's not really what the novel is about.