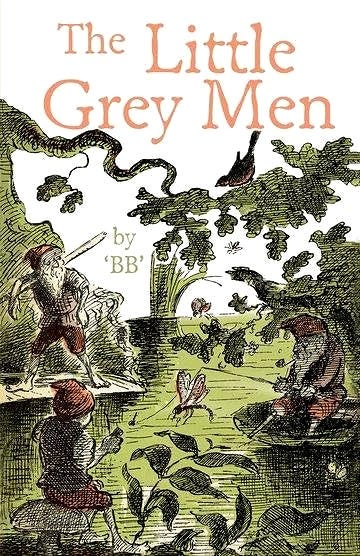

The Little Grey Men is one of those forgotten masterpieces by naturalist, artist, and author Denys James Watkins-Pitchford, writing under the pen-name B.B. The book was published in 1942, in the midst of WWII, and won the Carnegie Medal for that year. It follows the adventures of three gnomes, Sneezewort, Baldmoney, Dodder, “the last gnomes left in Engl…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A kind of elvish craft to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.