On Tolkien's Letter 131 (3): Gods and Heroes out of the Sea

Beowulf, Scyld Sceafing, and the Númenóreans

I’ve been spending a lot of time with Tolkien’s letter #131 lately. This is his extraordinary 10,000-word letter to Milton Waldman written in 1951, now fully published in the revised edition of Tolkien’s letters: The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded edition (2023). This piece is one of a series of thoughts on ideas Tolkien explores in this letter.

As I briefly mentioned in my previous piece in this series, in his letter to Milton Waldman, Tolkien presents an overview of his own Middle-earth mythology as a coherent, standalone body of work. However, he also pauses every now and then to offer parallels with real-world mythological and folklore motifs (which is a great boon for scholars - Tolkien wasn’t that keen on identifying his own sources). When he reaches the Second Ages of Middle-earth, he has the following to say about the Númenóreans:

In the first stage, being men of peace, their courage is devoted to sea-voyages. As descendants of Earendil, they became the supreme mariners, and being barred from the West, they sail to the uttermost north, and south, and east. Mostly they come to the west-shores of Middle-earth, where they aid the Elves and Men against Sauron, and incur his undying hatred. In those days they would come amongst Wild Men as almost divine benefactors, bringing gifts of arts and knowledge, and passing away again – leaving many legends behind of kings and gods out of the sunset.

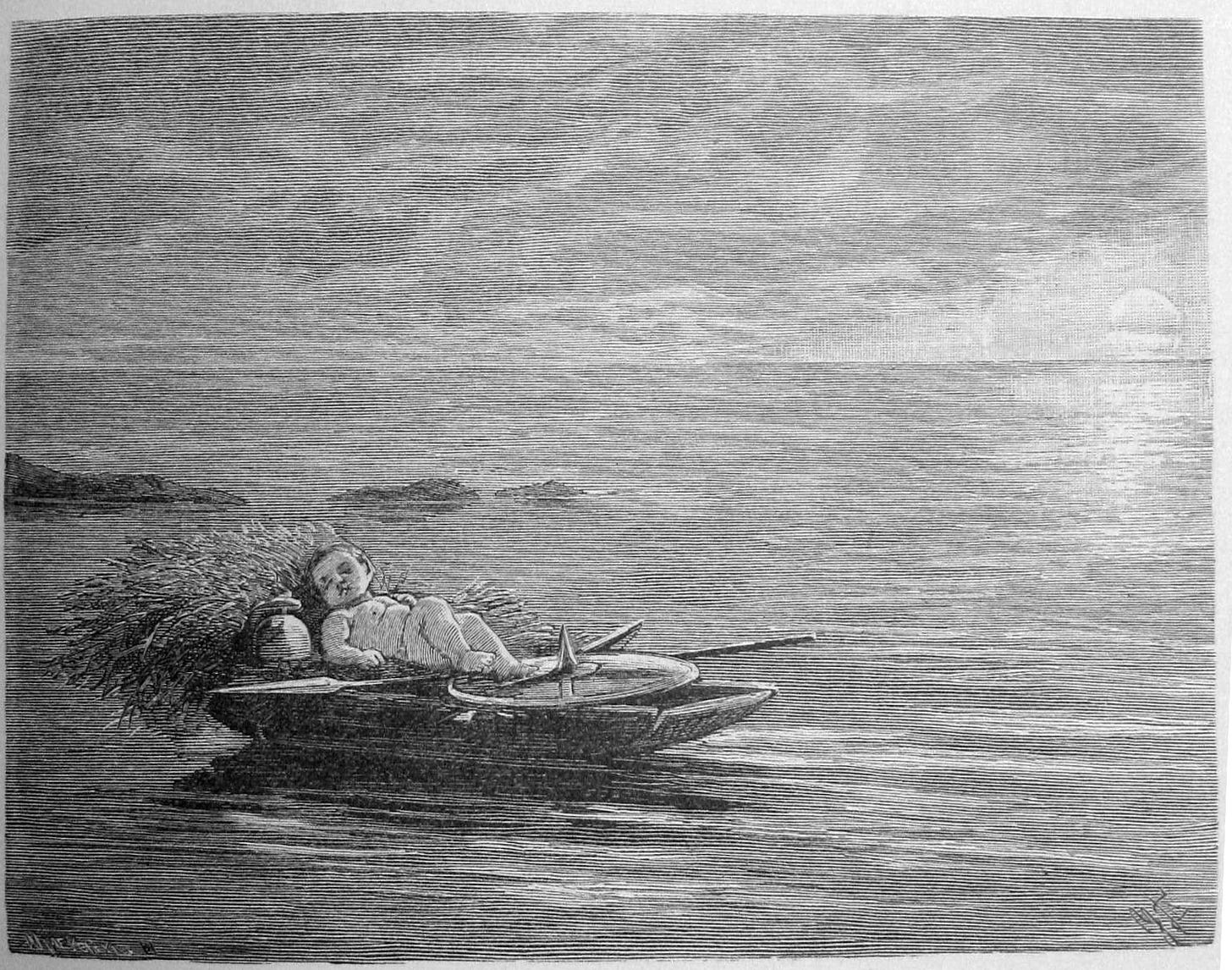

Tolkien was particularly interested in this motif, the idea of the god or hero coming out of the sea from some unknown land as an infant (placed in a boat), in order to offer knowledge (often very practical knowledge) to the society that takes him in, before sailing back across the sea to that unknown, mysterious place at the point of death. Many readers, of course, will make an immediate link with the ending (or one of the endings!) of the King Arthur cycle of legends: Arthur is mortally wounded in his final battle against Mordred at Camlann, but he sails to Avalon to be healed1. But Arthur’s story doesn’t start with a baby coming out of the sea. That storyline is perhaps best known by the character that Tolkien had in mind more specifically: Scyld Scefing in the opening of the epic poem Beowulf, whose name also appears as Scef, Scéaf or Scéafa in other Old English and Old Norse texts.

Here’s how Scyld’s storyline is given (in very condensed form) in the opening scenes of Beowulf. We hear of Scyld the exalted king, who has died and is being prepared for his ship funeral. The translation I quote from here is Tolkien’s own (in prose):

There at the haven stood with ringéd prow, ice-hung, eager to be gone, the prince’s bark; they laid then their beloved king, giver of rings, in the bosom of the ship, in glory by the mast. There were many precious things and treasures brought from regions far away; nor have I heard tell that men ever in more seemly wise arrayed a boat with weapons of war and harness of battle; on his lap lay treasures heaped that now must go with him far into the dominion of the sea. With lesser gifts no whit did they adorn him, with treasures of that people, than did those that in the beginning sent him forth alone over the waves, a little child. Moreover, high above his head they set a golden standard and gave him to Ocean, let the sea bear him. Sad was their heart and mourning in their soul. None can report with truth, nor lords in their halls, nor mighty men beneath the sky, who received that load.

So here we have in a very efficient, laconic way, in a few lines only, really, the entire story of the baby sent from over the sea by unknown (but clearly supernatural) powers to benefit the people who received him. “Those that in the beginning sent him forth alone over the waves” are unknown, mysterious, and no one knows who they are at the end of Scyld’s life, when the same mysterious “those” receive his remains across the sea.

In Beowulf, Scyld Scefing is an illustrious king, an ancestor of important royal lines, but both here and in other texts he also seems to be a semi-divine figure: a “corn god” or cultural hero, who comes from the unknown to bring gifts and crafts of agriculture and cultivation of grains. “Shefing” of course, means “of the sheaf [of grain]” and his son’s name in Beowulf, Beow, means barley. In addition, in some texts, when he appears as a baby on a boat, he sleeping with a sheaf of grain by his head (see Figures 1 and 2).

In one of my published articles I have traced how Tolkien’s concept of the Undying Lands in the Uttermost West, Valinor and Tol Eressëa in his legendarium, were an opportunity for him to merge the Germanic traditions of the god/hero coming out of the sea (and returning to some mysterious land there upon death) with the idea of the Otherworld journey across the sea in Celtic tradition, mostly in Irish texts, but found in some Welsh sources too.2 Tolkien’s unfinished novel The Lost Road (1930s) is perhaps the most explicit evidence for this “merging of traditions”, as I have called it.

The Lost Road is a time-travel story, involving a series of fathers and sons (always bearing names that could be translated as “Bliss-friend” and “Elf-friend”) re-living (by means of dreams) old myths and legends, concluding with the fall of Númenor. Tolkien only wrote two parts of the book: the “opening chapters,” concerning a father and son of modern times, Alboin and Audoin, and the “Númenórean chapters,” concerning Elendil and Herendil of Númenor. Nevertheless, in his notes and drafts of the “unwritten chapters” in-between, Tolkien lists the Germanic and Celtic mythological material he was planning to reshape and adapt, including the legend of King Sheave (Scyld Scefing), the Old English poem The Seafarer, the Irish immram (otherworld voyage) tradition (the voyage of St. Brendan in particular), and tales of Tir-nan-Óg (one of the names of the Irish otherworld). As I write in my earlier article:

It seems that by incorporating in his legendarium the Celtic tradition, Tolkien was able to establish a pagan, pre-Christian otherworld that the Anglo-Saxons also knew, and that the poets of The Seafarer and Beowulf alluded to, a land where the real Elves were, a land that was central in his conception of “a mythology for England”.

When Tolkien’s The Fall of Arthur was published, it became clear that Tolkien also linked the Arthurian motif of the return to Avalon to this merging of mythological figures, as I examined in a previous talk.3

Given Tolkien’s enduring fascination with that “other”, semi-divine place across the sea (be it Tir-nan-Óg, or the place whence Scyld came, or Arthur’s Avalon, or Valinor and Tol Eressëa) it’s perhaps not surprising to see him reflecting on this same theme when he outlines the story of the Númenóreans in letter #131. He describes them landing upon Middle-earth on their great ships, and seeming to the “Wild Men” there as “almost divine benefactors”, bringing knowledge, gifts and crafts (most importantly, agriculture, stonemasonry and ironmongery, according to The Silmarillion). The Númenóreans are, then, very much “culture heroes”, like Scyld Scefing, and they eventually depart back to their wondrous island, leaving behind them legends “of kings and gods out of the sunset”. Númenor is not Valinor, of course, but it’s close enough to the Undying Lands to grand the Númenóreans longer life and a paradisal existence (until all goes pear-shaped, when they defy the ban of the Valar). Númenor, therefore, is another chance for Tolkien to “explain away” that unknown land across the sea whence gods or culture heroes originate in real-world mythological traditions. If we go with Tolkien’s conceit that Middle-earth is not an imaginary world, but our own world at some point in a mythical past4, then the Númenóreans may have supposedly inspired legends of our own Primary World, of “corn-gods” or culture heroes coming out of the sea.

The imagery is so important to Tolkien that he repeats it in letter #131, when he summarises the Third Age of Middle-earth, i.e., the events of The Lord of the Rings. When he reaches the siege of Gondor, he notes:

The siege is raised at the last moment by the coming at last of the Riders of Rohan, led by their ancient king Théoden. The charge of their horsemen saves the field. Then the great battle of the Pelennor Fields is joined. Théoden falls. Victory turns towards the Enemy, but Aragorn appears in the Great River with a fleet, coming as the Númenóreans of old as it were up out of the Sea, and he raises for the first time in many ages the Banner of the King.

Needless to say, Aragorn is a descendant of “the Númenóreans of old”, and though he comes out of the River Anduin, rather than out of the sea, his arrival evokes once more the spectacular vision of the “culture hero”, the divinely appointed king, emerging out of water in majestic vessels.

Granted, the legend of Scyld Scefing is not mentioned by name in letter #131, but I think it is strongly hinted by the imagery of heroes and kings “out of the sunset” (i.e. from the West), or “out of the Sea”, and more so considering Tolkien’s continuous interest in this motif.

It should be noted that the Númenóreans and the Men of Gondor are connected with historical Germanic peoples too, specifically the the Vikings, who were renowned for their legendary ships and naval prowess (I have discussed this at length in my book, Tolkien, Race and Cultural History). But I think that in letter #131 Tolkien is mostly thinking of mythological/legendary parallels for his legendarium, with the otherworldly, mysterious land beyond the sea as a touchstone that brings together different European folkloric traditions in Middle-earth.

This is, of course, an ambiguous ending that often gave rise to ideas of Arthur as the Once and Future King, the righteous king who will come back to save his people in the future.

See “Tolkien’s ‘“Celtic” type of legends’: Merging Traditions”, originally published in Tolkien Studies 4 (2007): 51-71, now available to read free of charge here.

See my book Tolkien, Race and Cultural History for more on this, especially chapter 10: “Visualizing Middle-earth: Real and Imagined Material Cultures”.