I’ve been spending a lot of time with Tolkien’s letter #131 lately. This is his extraordinary 10,000-word letter to Milton Waldman written in 1951, now fully published in the revised edition of Tolkien’s letters: The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded edition (2023). This piece is one of a series of thoughts on the ideas Tolkien explores in this letter.

I’ve been recently working on a a big Tolkien editorial project, involving multiple Tolkien scholars, and approaching Tolkien’s work from different perspectives: from biographical and historical/contextual angles, to worldbuilding, critical/theoretical lenses, and questions of adaptations and legacies. My own chapter focuses on Tolkien’s “Mythologies”, and the many ways this term can be understood (and what it can tell us about Middle-earth and the entire legendarium). Consequently, I’ve been spending a lot of time reading closely and contemplating Tolkien’s 1951 letter to Milton Waldman (Letter #131), in which he summarises his mythology (as he conceived it at that point) and reflects on his own creative process. In the next few weeks, I will be sharing thoughts and ideas that have arisen from my recent close reading of letter #131, based on particular quotations, and linking those with wider themes and questions in Tolkien’s writings and scholarship.

Let me begin today with a tiny quotation from the letter, which is rich with ideas to explore. As Tolkien summarises The Lord of the Rings (already finished by that point) for the benefit of his reader, Milton Waldman, he eventually comes to the point where the Fellowship reach Lothlórien, and he writes:

Aragorn leads them on through Lórien, a guarded Elvish land – at which point I make the perilous and difficult attempt to catch at close quarters the air of timeless Elvish enchantment;

There is something deeply interesting in this brief quotation. Tolkien seems to be echoing here his own words from his earlier essay, “On Fairy-stories”1, in which he describes Faërie (“the realm or state in which fairies have their being”) as a “Perilous Realm” or “perilous land”, that cannot be caught in words. Tolkien doesn’t evaluate his own effort to represent “Elvish enchantment” in Lothlórien either. He calls the attempt itself “perilous and difficult” but he doesn’t pass judgment on the resulting chapters in The Fellowship of the Ring2. So let us look at just one passage where, I think, this attempt begins in the text, just as the fellowship have been led into Lothlórien, blindfolded, by Haldir:

The others cast themselves down upon the fragrant grass, but Frodo stood awhile still lost in wonder. It seemed to him that he had stepped through a high window that looked on a vanished world. A light was upon it for which his language had no name. All that he saw was shapely, but the shapes seemed at once clear cut, as if they had been first conceived and drawn at the uncovering of his eyes, and ancient as if they had endured for ever. He saw no colour but those he knew, gold and white and blue and green, but they were fresh and poignant, as if he had at that moment first perceived them and made for them names new and wonderful. In winter here no heart could mourn for summer or for spring. No blemish or sickness or deformity could be seen in anything that grew upon the earth. On the land of Lórien there was no stain.

I have highlighted in bold the particular words and phrases from this extract that caught my attention in this (umpteenth) re-read of this part of The Lord of the Rings. Let me offer some thoughts on some of those:

Stepping through windows

I was intrigued anew by the idea of “stepping through a high window”. There’s something incongruous about the word-choice here: we usually step through a door, not through a window. Still, a window, just like a door, is a passage, a kind of threshold, or even portal. Stepping though that kind of passageway can lead you somewhere else. Perhaps only just outdoors, or indoors. But in fantasy literature, doors, windows, and all sorts of other things with frames or borders around them (paintings, wardrobe doors, rabbit holes, mirrors) can lead you to an otherworld, an imaginary elsewhere.3

What we seem to have in this Lord of the Rings passage, therefore, is an otherworld inside an otherworld. Middle-earth is an immersive fantasy world right from the opening of The Lord of the Rings, when we find ourselves in the Shire and then out to an expansive mediaevalesque Secondary World with its own history, cultures, legends, languages, flora and fauna, etc. But Lothlórien is a world upon itself, a glimpse of a “vanished world”, as the narrator’s voice tells us, and Frodo feels like he’s stepped through a strange portal to reach it: this is conveyed via the oxymoronic image of “stepping through a window”.

But it’s not just the window that makes the image strange, noteworthy. It’s also a “high” window. Surely one has to climb up somehow to step through a high window? Why is the window high? Does the figure of speech here (it’s a simile after all) point to a tall building, a tower perhaps, with a window high up? If so, this brings to mind Tolkien’s famous allegory of the tower in his Beowulf lecture4: in this image, the epic poem Beowulf itself is likened to a tower made up of disparate material from different time-periods, and the critics are compared to archaeologists who bring down the tower to examine every part of its construction, dating its materials and explaining how it was made. But for Tolkien this misses the point of the poem as is stands, as a work of literary art. He concludes his allegory (or extended metaphor, if you wish) by saying that: “But from the top of that tower the man had been able to look out upon the sea.”

Is there a link, then, in this fleeting simile in The Lord of the Rings, with the idea of the tower of amalgamated folkloric and literary sources to create a new, remarkable work of art, that can let you glimpse new horizons? Perhaps. Lothlórien is, after all, Tolkien’s version of Faërie, the “Perilous Realm”, inside Middle-earth. Faërie becomes reconfigured and reconstructed every time a fairy-tale is told or retold, bringing together traditional material and new inventions. And Lothlórien itself has been compared to hidden/timeless fairy realms in European folklore, elements in Celtic-language medieval sources, and even religious/spiritual visions of the Earthly Paradise. It is, itself, a tower made of disparate material, but all reshaped and combined with original elements to make up a memorable new version of Faërie.

There is a lot going on in this short phrase/simile, then. Consider it again, keeping in mind all of these potential links and allusions: “It seemed to [Frodo] that he had stepped through a high window that looked on a vanished world”'.

The affordances of language (and art)

It’s not surprising for Tolkien to contemplate how language can (or cannot!) deal with what Frodo experiences at that moment. After all, both Tolkien’s academic and a lot of his creative life revolved around language, its construction, history, evolution, entanglement with literature, etc.

In this Lord of the Rings extract, Frodo cannot find the words to describe the light he sees in Lothlórien: “his language had no name” for it. This is, once more, an idea that links back to “On Fairy-stories”, in which Tolkien writes that: “Faërie cannot be caught in a net of words; for it is one of its qualities to be indescribable, though not imperceptible”.

Indeed, Frodo does perceive the land around him, and its indescribable light, and finds he needs new language to process it. The narrator’s voice focuses specifically on the colours Frodo sees: “He saw no colour but those he knew, gold and white and blue and green, but they were fresh and poignant, as if he had at that moment first perceived them and made for them names new and wonderful”. This is, perhaps, the most potent enchantment of Lothlórien: it seems both old and new at the same time, both “fresh” and “ancient”. Frodo, like a Biblical Adam, has to invent new names for the colours that he sees around him, but these colours are, nevertheless, familiar. We don’t have fantastical, inconceivable fantasy colours here, like Lovecraft’s “colour out of space”, or Susanna Clarke’s “colour of heartache”. Just the colours we all know, but somehow, different, “recovered” from the triteness of something overfamiliar5. Looking like they’re brand new.

This mention of colours brings us back, yet again, to “On Fairy-stories”, Tolkien’s theorising of how fantasy works and what it can do. In that essay, Tolkien lingers for a while on the power of language to create fantasy, focusing especially on one particular part of speech: the adjective. He writes:

The human mind, endowed with the powers of generalisation and abstraction, sees not only green-grass, discriminating it from other things (and finding it fair to look upon), but sees that it is green as well as being grass. But how powerful, how stimulating to the very faculty that produced it, was the invention of the adjective: no spell or incantation in Faërie is more potent. And that is not surprising: such incantations might indeed be said to be only another view of adjectives, a part of speech in a mythical grammar. The mind that thought of light, heavy, grey, yellow, still, swift, also conceived of magic that would make heavy things light and able to fly, turn grey lead into yellow gold, and the still rock into a swift water. If it could do the one, it could do the other; it inevitably did both. When we can take green from grass, blue from heaven, and red from blood, we have already an enchanter’s power – upon one plane; and the desire to wield that power in the world external to our minds awakes. It does not follow that we shall use that power well upon any plane. We may put a deadly green upon a man’s face and produce a horror; we may make the rare and terrible blue moon to shine; or we may cause woods to spring with silver leaves and rams to wear fleeces of gold, and put hot fire into the belly of the cold worm. But in such ‘fantasy’, as it is called, new form is made; Faërie begins; Man becomes a sub-creator.

So the fantasy author creates a new Secondary World out of familiar elements, but mixed up in unexpected ways, approached from a new angle, relying on oxymorons and things we know as impossible in our mundane reality.

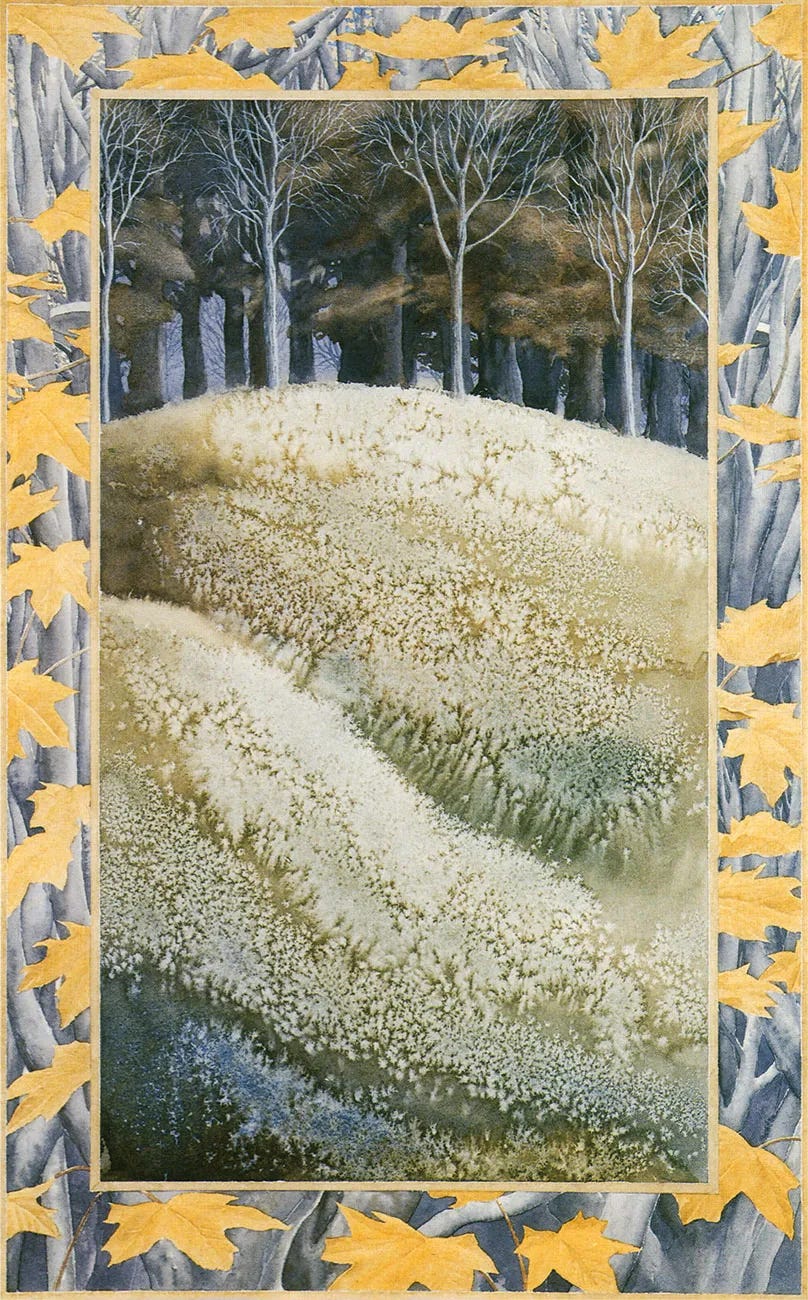

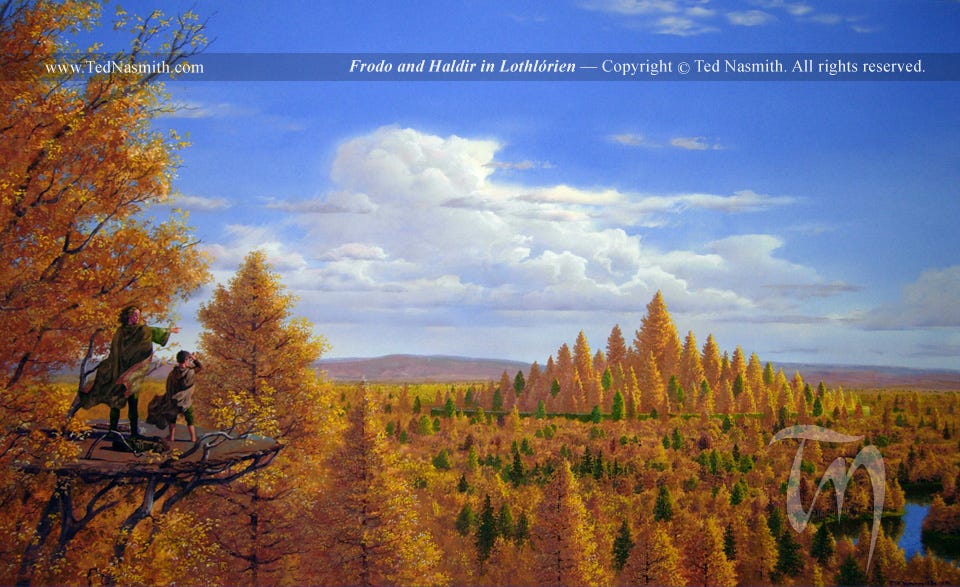

Frodo, of course, is only trying to describe the colours he sees in Lothlórien, he is not trying to create Lothlórien out of language - or is he? I wonder, isn’t every new description, conceptualisation, invention of new words (or rearrangement of old words in a new way) to capture something, a re-creation of an experience? It’s also significant, I think, that Lothlórien seems to Frodo as if it has just been “conceived and drawn”: notice the word “drawn” here, a word connected with the visual arts. It is as if an artist (Niggle perhaps?) had come up with a vision of this land and had just drawn in while the inspiration was still powerful. Tolkien himself, of course, was an artist (despite his self-deprecating words about his own talent) and also attempted a drawing of “The Forest of Lothlórien in Spring” (see below) - a version of Lothlórien the Fellowship doesn’t see (they reach it in winter). The link between verbal and visual imagination is something we see at work in Tolkien’s worldbuilding time and time again, so it’s really lovely to notice it in this passage too.

Nature perfected

Last but not least, I was also struck by this passage’s references to nature, not just the new flora the fellowship encounter in the previous paragraph (Haldir refers to “the yellow elanor, and the pale niphredil”) but the sentiments the narrator’s voice expresses in the quotation I am focusing on here. We read that: “In winter here no heart could mourn for summer or for spring”. Most of us would think of nature’s glory in the spring or summer, when all is in bloom in the warmth of the sunshine. Autumn often seems like a time of lamentation - there is plenty of poetry responding to this sentiment. And winter seems like a time of death, of nature falling asleep before it can re-awaken again in spring. But Lothlórien is equally beautiful in the winter - it’s actually January when the fellowship reach it.

What is more, the land suffers “no blemish” or “deformity”. Tolkien was a gardener and was keenly aware that the natural world around us, wonderful as it is, is not free of deformity, sickness, or “stain”, as the passage puts it. Trees die, invasive species wreak havoc on local flora, pests attack, diseases are sometimes unstoppable. The natural world isn’t perfect, however much we try to learn how to manage, curate and tame it in our gardens. Lothlórien is different: it is the ideal state of nature, the one any gardener would dream of. And yet it’s not a wild space either - it’s a garden of sorts, looked after, managed, perfected by the Elves. No wonder one can think of Lothlórien as an Earthly Paradise - it is a glimpse of Valinor in Middle-earth.

I could spend a lot more time just on this one passage from The Lord of the Rings. I could talk about word choice, for example. About how Tolkien uses the words “shapely” and “shapes” in close proximity, and how the meaning slightly changes and transforms as we move from the derivative word towards the base one. How the repetition of sound draws your attention to this word choice. I would also happily spend more time on the idea of the “fragrant” grass in Lothlórien, as if it’s spring, though we’re in the middle of winter. And I could also stop to remark on how Frodo stood there “awhile”, lost in wonder, as he encountered the land. How long is “awhile”, I wonder? Especially when time is so slippery and unpredictable in Lothlórien?

But I will stop here for now. I think it’s time for me to give up trying to capture the enchantment of Lothlórien in my own words too. It shall remain “indescribable, though not imperceptible” with each reading.

“On Fairy-stories” was originally delivered in 1939 as part of the Andrew Lang Lecture series is held at the University of St. Andrews. It has been published in different formats (and slightly different versions), but the best current edition is Douglas A. Anderson’s and Verlyn Flieger’s “extended” edition, Tolkien On Fairy-stories (HarperCollins, 2008).

Book II, chapters 7-9, “Lothlórien”, “The Mirror of Galadriel”, and “Farewell to Lórien”.

I have explored this idea, especially what kind of objects/thresholds made good portals in fantasy literature, in my essay “Fantasy Worlds: Crossing Borders of Otherness” published in Realms of Imagination: Essays from the Wide Worlds of Fantasy, edited by Tanya Kirk and Matthew Sangster (British Library Publishing, 2023).

“Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”, published in The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays, edited by Christopher Tolkien (HarperCollins, 2007 [first published in 1983]).

I am nodding to another part of “On Fairy-stories” here, of course: the idea of fairy-stories (and fantasy literature) offering “recovery”, allowing us to see the familiar world anew, and marvelling at things that have become trite: trees become Ents.