It’s Bloomsday today, the date on which James Joyce’s 1922 novel Ulysses is set. Joyce’s protagonist, Leopold Bloom, gives his name to this annual commemoration of Joyce’s work, specially celebrated in Dublin (with the Bloomsday Festival), but also elsewhere in the world.

Though seemingly an unlikely duo, Tolkien was at least interested in Joyce’s work, and I have been researching and writing about Tolkien’s engagement with Joyce for a while. To mark this day, I am summarising below some of the key meeting points between these two writers, with links to further resources if you want to know more.

Tolkien’s mentions of Joyce

The first time I realized there was a fruitful Tolkien-Joyce connection was when I was still doing my PhD (2002-2005) and I was researching the notes and manuscripts of Tolkien’s paper on linguistic invention, “A Secret Vice”, which he delivered in 19311. Among drafts and scattered pieces of paper in the relevant Bodleian folder, I saw that Tolkien had scribbled not Joyce’s name itself, but the name of one of the characters from what later became Finnegans Wake: Anna Livia Plurabelle2.

But we now know this was not the only time Tolkien made a note of this name: it also appears transcribed in his “Qenya Alphabet” (later known as “tengwar” letters) in a document also dated 1931, now edited and published as a facsimile in the journal Parma Eldalamberon, vol. 203.

Now, there’s an interesting point to be made about dates here. Finnegans Wake wasn’t published as a finished novel with this very title until 1939. How could Tolkien be citing his character’s name in/around 1931? Joyce started writing Finnegans Wake roughly a year after the publication of Ulysses and during its long gestation he called it “Work in Progress”. Already from 1924, fragments from “Work in Progress” appeared in different publications. The section known as “Anna Livia Plurabelle” had already been published four times by the time Tolkien delivered “A Secret Vice”:

in the periodical Navire D’Argent (October 1925)

in the avantgarde journal transition (November 1927)

as a separate booklet by Crosby Gaige in New York in 1928

also as a booklet by Faber and Faber in London in 1930.

It seems that Tolkien was familiar with at least one of these publications, some of which were acquired by the Bodleian Library soon after they were released.

Why was Tolkien interested in Joyce?

Now, Tolkien mentioning a particular name that may have impressed him out of Joyce’s work is one thing. It may be that there was a sense of euphony or “linguistic aesthetic” in the name “Anna Livia Plurabelle”, that made it particularly pleasant or memorable to Tolkien. But I think there was something more going on to draw Tolkien’s attention to Joyce. Joyce was a modernist author who made a notorious name for himself as radical, experimental, obscure. He was also more-or-less on the opposite side of the political spectrum to Tolkien. Still, they both shared a keen interest: linguistic experimentation.

As is well-known, Tolkien invented a number of languages for the peoples of his Middle-earth legendarium, with different degrees of detail. Most readers are familiar with Quenya (a language shaped by Finnish, as well as Latin and Greek), and Sindarin (very much phonetically influenced by Welsh). These two languages feature in The Lord of the Rings. But, of course, Tolkien sketched and developed other languages too, such as Khuzdul (Dwarvish), the Black Speech, etc.4

Joyce, on the other hand, saw himself as the creator of, perhaps not his own invented languages, but at least of his own linguistic idiom. It is not an exaggeration to say that for Joyce – especially in his later writings – literature was an experiment in language. After the stream-of-consciousness and inventive use of onomatopoeia in Ulysses, Joyce embarked on Finnegans Wake, perhaps his most ambitious project, in which, as he declared, he wanted to “invade the world of dreams” and therefore had to “put the language to sleep”.5

Joyce’s linguistic experimentation has often been discussed as an attempt at a “universal language”, a language that would bypass the “curse” of Babel and would allow all humankind to communicate easily. Tolkien’s linguistic inventions have also been discussed as part of the same tradition6. Indeed, Joyce himself expressed his wish to create “a language which is above all languages, a language to which all will do service”7. Finnegans Wake in particular is deliberately polyglot: John Bishop8 has identified Joyce’s playful use of over forty languages and dialects. In addition, the novel includes a plethora of neologisms based on punning, onomatopoeia, portmanteau techniques, and manipulating homonyms and etymologies, as well as creative and often humorous distortions of grammar9. Joyce was particularly fascinated by the “problem of Babel”, and Finnegans Wake contains a number of references and allusions to International Auxiliary Languages (languages made-up to facilitate international communication) such as Esperanto, Volapuk, Ido, Idiom Neutral and Basic English10. We know, of course, that Tolkien was also a learner and early supporter of Esperanto, and in his “Secret Vice” talk/notes (and in his letters) mentions other such languages too (e.g. Novial).

Joyce was also interested in linguistic theories of his time about the origins of language, and was particularly attracted to the idea that human speech originated in gestures, especially after attending lectures by Marcel Jousse and (like Tolkien) reading the work of Sir Richard Paget11. Joyce was equally well-versed in the writings of important nineteenth-and early twentieth-century philologists and linguists Tolkien knew, including Max Müller and Otto Jespersen12.

Tolkien, Joyce, and the “Language as Art” vs. “Language as Communication” Question

Tolkien and Joyce, therefore, shared enough interests to make the former look into the latter’s work. But there was a crucial difference: Joyce was more interested in language as art, even if devoid of meaning. Tolkien was also keenly interested in language as art, and strived to achieve a specific sense of “linguistic aesthetic” in his invented languages, but he was interested in meaning. His Middle-earth languages were constructed to be spoken (or recited, in the case of poetry) but could be translated (though sometimes Tolkien doesn’t give us all the tools we need to do so!) and make sense. It was a tight link between new sounds and a definite meaning (whether the reader understands it or not, and whether profound or trivial) that Tolkien was striving for in his invented languages.

Joyce, on the other hand, wasn’t necessarily interested in coherent, objective meaning. He loved playing with the sounds of language (without going as far as inventing a new language), but he manipulated modern English to suit his purposes, and these purposes were different to Tolkien’s. For Joyce, as implied above, the purpose seems to have been an “escape” from the English language which he saw as another tool of domination over the Irish, erasing cultural differences. He wrote: “I cannot express myself in English without enclosing myself in a tradition”13. At the same time, he wanted to inject English with a large dose of cosmopolitanism – varying from foreign words to neologisms – in an attempt to express the multi-lingual, “globalised” world of his time and the dangers of nationalism, which he saw as directly responsible for the Great War14.

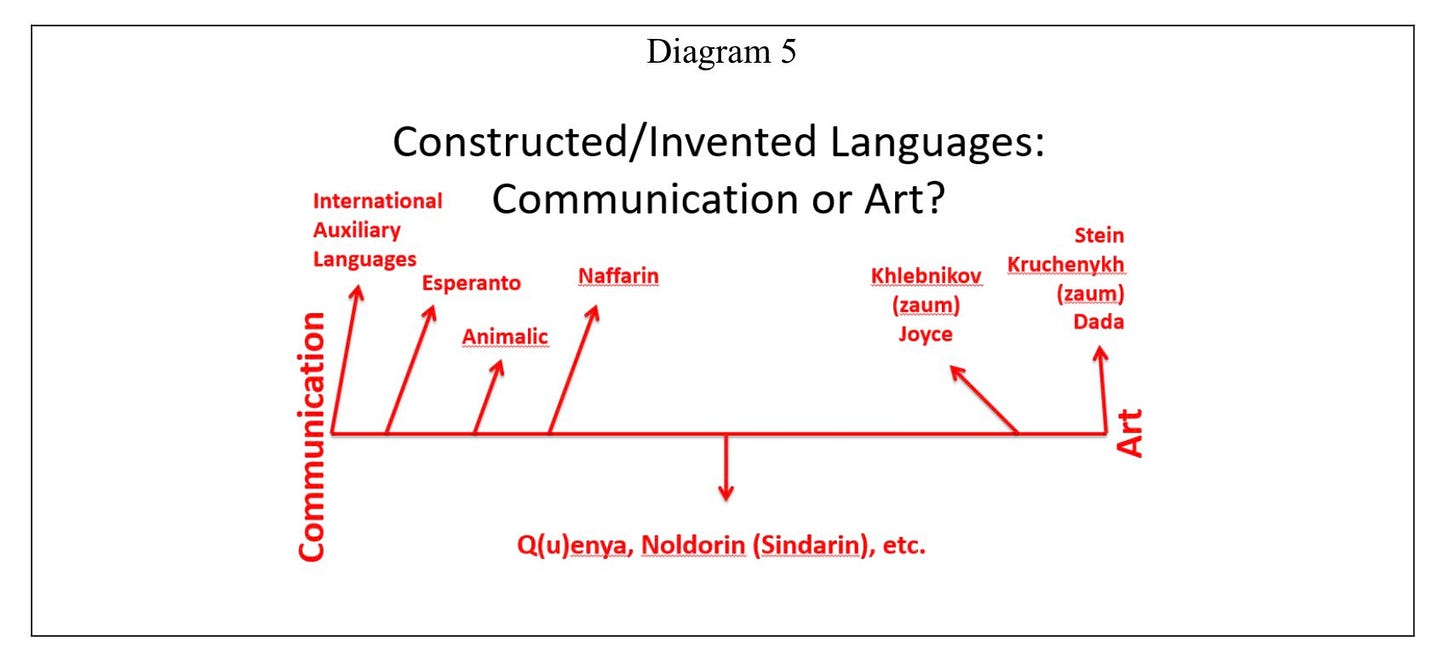

In my article “Language as Communication vs. Language as Art: J.R.R. Tolkien and early 20th-century radical linguistic experimentation”, I have actually constructed a diagram that shows not just Tolkien and Joyce, but also other early 20th-century language inventors/experimenters, whom I have placed in a continuum (see above). On one side of this continuum, is the extreme of “language as communication”, i.e. language as a utilitarian tool to facilitate our everyday lives, with meaning being the main focus. On the other side, I have placed “language as art”, experimenting with the sounds of language unaffected by the need for language to mean something objective, but more interested in its subversive affordances.

As you can see, Joyce’s work is closer to the side of language as art, though his work is not as extreme as that of other creative practitioners. Tolkien, though, I have situated squarely in the middle of this continuum. As I wrote in my 2018 article:

Qenya, Noldorin, and all the other languages Tolkien invented (or at least sketched) for his legendarium, are both artistic (made to produce “pleasure”, created to be beautiful, or at least symmetrical and coherent, with a specific “flavour” or “character”) while at the same time they are utilitarian – of course only spoken by imaginary people in a fictional context, but still, within the invented world of the legendarium, they are a tool for communication. Even if the reader cannot understand these invented languages, the author certainly does. […]

Or, as Tolkien put it himself, he was interested in:

making a ‘language’ in which the sounds do ‘mean’ something (though only perhaps to the author)15

The exact date of Tolkien’s first delivery of “A Secret Vice” was not known till I worked with Dr. Andrew Higgins on our edition of Tolkien’s talk, with its accompanying drafts, another brief essay on “Phonetic Symbolism”, etc. This edition was published by Tolkien’s official publishers, HarperCollins, as part of the Tolkien corpus, in hardback and (now) paperback.

Tolkien, J.R.R. (2016) A Secret Vice: Tolkien on Invented Languages, edited by Dimitra Fimi and Andrew Higgins. London: HarperCollins, p. 91.

Tolkien, J.R.R. (2012) ‘The Qenya Alphabet’, edited by Arden R. Smith, Parma Eldalamberon, 20 (PE 20), pp. 87-9.

For a brief introduction to Tolkien’s invented languages, including how they fit in the tradition of fictional languages, whether they preceded his Middle-earth mythology, as well as the way Tolkien constructed them, see Lecture 7 of my Audible course: The World of J.R.R. Tolkien.

Cited in Ellmann, Richard (1983) James Joyce. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 546.

See my own Tolkien, Race and Cultural History: From Fairies to Hobbits (London: Palgrave Macmillan), esp. Part II, Chapter 5, 6, and 7; my journal article “Language as Communication vs. Language as Art: J.R.R. Tolkien and early 20th-century radical linguistic experimentation” in the Journal of Tolkien Research (2018), and the the Introduction and notes I co-authored with Andrew Higgins for Tolkien’s Secret Vice edition.

Cited in Zweig, Stefan (1943) The World of Yesterday: An Autobiography. New York: Viking Press, p. 275.

Bishop, John (1986) Joyce’s Book of the Dark: Finnegans Wake. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

For an overview see Watt, Stephen (2011) ‘“Oirish” Inventions: James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Paul Muldoon’, in Adams, Michael (ed.) From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 169–73.

See Shaw Sailer, Susan (1999) ‘Universalizing Languages: “Finnegans Wake” Meets Basic English’, James Joyce Quarterly, 36:4, pp. 853–68; and Schotter, Jesse (2010) ‘Verbivocovisuals: James Joyce and the Problem of Babel’, James Joyce Quarterly, 48: 1, pp. 89–109.

Milesi, L. (2008) ‘Joyce’s English’, in Momma, H. and Matto, M. (eds.) A Companion to the History of the English Language. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, p. 474.

See essays in Van Hulle, Dirk (ed.) (2002) James Joyce: The Study of Languages. Brussels: P. I. E.-Peter Lang.

Cited in Zweig, The World of Yesterday, p. 275.

See my and Andrew Higgins’s Introduction to Tolkien’s A Secret Vice, p. lxiii.

Tolkien, A Secret Vice, p. 92.